The 1898 Augsburg Seminary Minnesota Supreme Court Decision

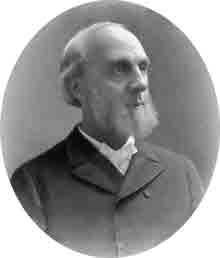

In 1898, there were six justices on the Minnesota Supreme Court: William B. Mitchell, Loren W. Collins, Daniel Buck, Thomas Canty, Charles M. Start, and Calvin L. Brown.[1]

Justice Charles E. Vanderburgh—the early supporter of Augsburg Seminary—had ended his service on the Minnesota Supreme Court in 1894.[2]

Justice Mitchell issued the opinion for the Minnesota Supreme Court, in which Justice Buck did not take part.

There were no dissenting opinions—although the concurring opinion of Justice Canty sounded much like a dissent.[3]

After the presentation of voluminous affidavits, and extensive oral arguments, on June 9, 1898, the Minnesota Supreme Court overturned the decision of the Hennepin County District Court, and declared that neither the Oftedal Trustees, nor the Competing Trustees elected by the United Church, were in control of Augsburg Seminary.

The persons in legal control of the Augsburg Seminary corporation were its five original incorporators—only one of whom was then a member of the Oftedal Trustees—Rev. Ole Paulson.[4]

The Minnesota Supreme Court’s reasoning for overturning the decision of the Hennepin County District Court—that the Competing Trustees for Augsburg Seminary elected by the United Church at its annual convention in 1896 were in charge of Augsburg Seminary—was based in part upon an obscure clause found in Article 4, Section 27 of the Minnesota Constitution of 1857:

No law shall embrace more than one subject, which shall be expressed in its title.

The effect of that constitutional provision was to defeat any claim that the trustees of Augsburg Seminary—whether elected by the Conference or the United Church—were anything more than mere agents of the corporation.

While such trustees were agents of the Augsburg Seminary corporation, they were not in control of the corporation. The Minnesota Supreme Court identified that five incorporators had organized a private charitable corporation pursuant to Gen. St. 1866, c. 34, tit. 3, and became a legal entity having the name: “The Norwegian Danish Evangelical Lutheran Augsburg Seminary.”[5]

Section 54 of the General Statutes of Minnesota 1866, Chapter 34, Title 3 identified the manner of incorporation, by providing in part as follows:

Any number of persons not less than three may associate themselves and become incorporated for the purpose of establishing and conducting colleges, seminaries, . . . as provided herein.

Section 55 of the General Statutes of Minnesota 1866, Chapter 34, Title 3 identified certain requirements for incorporators, and for Articles of Incorporation, by providing in part as follows:

They shall adopt and sign articles containing:

First. The name of the corporation, its general purpose and plan of operation, and its place of location.

Second. The terms of admission to membership and the amount of monthly, quarterly or yearly contributions required of its members. . . .

Fourth. The officers of the corporation or society, with time and place of electing or appointing the same, and the number of trustees or directors, if any, who are to conduct the transactions of the society during the first year of its existence.

Articles of Incorporation which were filed with respect to the Augsburg Seminary corporation identified a Board of Trustees consisting of five persons—the five incorporators being named as the first board of trustees—and fixed the time and place for the election of subsequent trustees, but were legally defective since such Articles of Incorporation did not expressly identify by whom any such successor trustees were to be elected, or provide for the admission of new members to the corporation.[6]

Section 56 of General Statutes of Minnesota 1866, Chapter 34, Title 3 identified the legal effect of the filing of the Articles of Incorporation, by providing in part as follows:

Upon filing said articles the persons named therein, and signing the same, become a body corporate with power to sue and be sued by its corporate name, to have a common seal which may be altered at pleasure, to establish by-laws and make all rules and regulations deemed expedient for the management of its affairs in accordance with law, and not incompatible with an honest purpose.

Therefore, even though Augsburg Seminary had to some extent existed informally since 1869, it had no legal existence as a corporate entity until 1872, when it was incorporated by five men—its members—who were also named as its first Board of Trustees.[7]

In 1877, an attempt was made to solve legal deficiencies relating to the election of successor trustees for Augsburg Seminary by the adoption of a curative act by the Minnesota legislature—one section of which ratified the election by the Conference of “trustees” for Augsburg Seminary.

However, that particular provision of the curative act was unconstitutional—in violation of Article 4, Section 27 of the Minnesota Constitution of 1857.[8]

Nevertheless, parts of the curative legislation adopted in various years, including in 1877, were constitutional, and had the effect of allowing the Augsburg Seminary private charitable corporation to be recognized as legitimate—de jure—under Minnesota law.[9]

The Minnesota Supreme Court discussed the purported Curative Act of 1877, by providing in part as follows:

Assuming, as we think the law is, that the first and second sections of Sp. Laws 1877 are valid under the doctrine of Green v. Boom Corp., 35 Minn. 155, 27 N. W. 924, they are purely curative or retrospective, and merely validate what had been done in the past.

The title of the act is wholly insufficient to embrace the prospective provisions of the third section, which is, therefore, wholly void under section 27 of article 4 of the constitution, even assuming that the legislature had the power to pass them under a proper title. [10]

If the Curative Act of 1877 had not violated the provisions of Article 4, Section 27 of the Minnesota Constitution of 1857, the decision of Hennepin County District Court might have been upheld, and the election of the Competing Trustees for the Augsburg Seminary corporation by the United Church could have been effective.

The Minnesota Supreme Court identified that Sections 1 and 2 of the purported Curative Act of 1877 were proper, since they were to be applied retrospectively only, by providing in part as follows:

Assuming, as we think the law is, that the first and second sections of Sp. Laws 1877 are valid . . . they are purely curative or retrospective, and merely validate what had been done in the past.

However, the Minnesota Supreme Court identified that Section 3 of the purported Curative Act of 1877 was unconstitutional, because it went beyond the subject matter of the legislation as identified in its title, by providing in part as follows:

The title of the act is wholly insufficient to embrace the prospective provisions of the third section, which is, therefore, wholly void under section 27 of article 4 of the constitution, even assuming that the legislature had the power to pass them under a proper title.

The Minnesota Supreme Court addressed the deficient filing of amended Articles of Incorporation for the Augsburg Seminary corporation in 1885, by providing in part as follows:

The attempted amendment of the articles of incorporation in 1885 by the trustees elected by the conference in and of itself amounted to nothing, for even conceding that they were trustees de facto, [but not de jure] they were the mere agents of the corporation, and had no power to amend the articles.[11]

The Minnesota Supreme Court then discussed the election of trustees for the Augsburg Seminary corporation by the Conference prior to the formation of the United Church, and the limited legal rights actually held by such trustees, by providing in part as follows:

The “incorporators” or “trustees” reported to the conference in June, 1873, what they had done, and the reason therefor, to wit, for the purpose of holding the legal title of the seminary property for the conference.

It does not appear that the conference took any formal action approving what had been done, but it made no objection, and by its subsequent conduct acquiesced in and approved of it.

At that meeting, and annually thereafter for nearly 20 years, the conference elected trustees, who, under its direction, had the exclusive management and control of the property and temporal affairs of the seminary, and annually made a report to the conference of what they had done.

They took the title to all property donated or contributed for the extension or maintenance of the seminary in the corporate name. [12]

The Minnesota Supreme Court determined that the five original incorporators of 1872 were the only members of the Augsburg Seminary corporation, and no other persons had the legal right to amend the Articles of Incorporation for the Augsburg Seminary corporation.[13]

The Minnesota Supreme Court also addressed the filing of amended Articles of Incorporation for the Augsburg Seminary corporation in 1885 by the trustees of Augsburg Seminary, and the limited power of such trustees, by providing in part as follows:

The attempted amendment of the articles of incorporation in 1885 by the trustees elected by the conference in and of itself amounted to nothing, for even conceding that they were trustees de facto, [but not de jure] they were the mere agents of the corporation, and had no power to amend the articles.[14]

The Minnesota Supreme Court discussed the filing of amended Articles of Incorporation for the Augsburg Seminary corporation in 1892, highlighting the provisions of Article II:

Finally, the five original incorporators, upon the theory that they were the sole members of the corporation, met, and amended the articles of incorporation by providing, among other things, that

“any person who is a member in good standing of a Norwegian Lutheran church connected with the United Norwegian Lutheran Church of America may become a member of this corporation by being elected as such member by a majority vote of the then members of the corporation, and by his acceptance in writing of such election: provided, that as soon as, and whenever, the members of the corporation shall exceed thirty in number, a two-thirds vote of such members shall be necessary in order to elect new members.” [15]

In other words, in 1892 the 5 original incorporators amended the Articles of Incorporation in order to allow for the admission of new members by the 5 original members, and then admitted 25 new members of the Augsburg Seminary corporation.

The Minnesota Supreme Court declared that such action by the 5 original incorporators was the first time that they had exercised any corporate powers since the original Articles of Incorporation were adopted in 1872.[16]

The election as trustees of four of the five Oftedal Trustees was made by the 30 “alleged members” of the Augsburg Seminary corporation authorized by the 1892 amendments to the Articles of Incorporation, with the fifth trustee claiming his appointment pursuant to the 1895 amendments to the Articles of Incorporation the Augsburg Seminary corporation.[17]

Article II of the 1892 amended Articles of Incorporation for the Augsburg Seminary corporation also provided for successors to the members of the corporation, by providing as follows:

In case of the death, incapacity to act, or permanent removal from the United States of America of a member of this corporation his membership shall thereupon cease and terminate, and a new member shall be elected in his place.

For good and sufficient reasons, the members of this corporation made by a two-thirds vote at any time remove any member and terminate his membership in the corporation and elect a new member in his place.

The Minnesota Supreme Court then identified the 1896 election by the United Church of the Competing Trustees for the Augsburg Seminary corporation, by providing in part as follows:

The conference of the United Church made no attempt to elect trustees of the seminary until its annual meeting in June, 1896, at which it elected the relators to the office (the plaintiffs in 1897 Hennepin County District Court action), the terms of office of all the last board elected by the old conference before the union having then expired.[18] . . .

This proceeding is an information in the nature of quo warranto, instituted by the relators against the respondents (appellants here) to oust them from the offices of trustees of a corporation called the Augsburg Seminary, and to induct the relators into the offices.[19]

The Minnesota Supreme Court identified that the only relevant issue in the case before it was the proper identification of the members of the Augsburg Seminary corporation, by providing in part as follows:

But the sole question here is, which of the parties, relators or appellants, have the title to an office in a private corporation?

The relators must, therefore, show title in themselves before they can properly inquire by what authority the respondents (appellants here) exercise their office.[20]

The Minnesota Supreme Court declared that only the members of a corporation have the power to elect the governing body of the corporation:

The power to elect the trustees or directors of a corporation belongs (at least in the absence of a statute providing otherwise) exclusively to the members of the corporation.[21]. . . Our conclusion is that, the relators having failed to show any title to the offices in themselves, the order appealed from should be reversed, and the proceedings remanded, with directions to the court below to quash the information. It is so ordered.

The rationale for the court’s decision can be summarized as follows:

- The Competing Trustees had a duty to demonstrate that they had a right to the office of trustees before they could challenge the title of the Oftedal Trustees.

- Those parts of the third section of the Curative Act of 1877 which were prospective in nature, and purported to confirm the election of trustees for the Augsburg Seminary corporation by the Conference, were invalid, because they were not expressed in the title of the act.

- The trustees of a corporation are merely its agents, and have no authority in themselves to amend the articles of incorporation.

- The custom and course of dealing of the Conference to elect the trustees of the Augsburg Seminary corporation—even though it was acquiesced in by the original incorporators for over 20 years—did not make as members of the corporation either the members of the Conference, or all of the members of the congregations belonging to the Conference, since custom and course of dealing cannot override statutory requirements.

- Neither the Curative Act of 1877, nor the general curative acts of 1881 or subsequent years, authorized the continuance of the usage or custom of electing trustees of the corporation by the Conference.[22]

During the course of the Court proceedings, much evidence was presented which was intended to identify those parties who were performing admirably in the discharge of their duties.

However, the Minnesota Supreme Court determined that such evidence was irrelevant:

The very voluminous record contains a vast amount of matter which we consider wholly irrelevant to the issues.[23]

Much evidence was introduced, and much is said in the briefs of appellants’ counsel, as to the alleged fact that the prosperity of the seminary and the donations towards its enlargement and support were largely the results of the efforts of the so-called “friends of Augsburg” prior to the union; also that the seminary is now being efficiently managed by the appellants.

Assuming all this to be true, we fail to see that it has any bearing on the legal issue in this case, which is the title to an office.[24]

The Minnesota Supreme Court then identified certain alleged hostile actions between the parties, which it also found to be irrelevant, by providing in part as follows:

The same may be said as to the alleged hostile acts of the United Church towards the seminary, since this controversy commenced by withdrawing their support from it, establishing another theological school, and expelling congregations and ministers for upholding the conduct of the appellants and the other “friends of Augsburg”; those things having nothing to do with the legal questions involved, and of their ethical character we are not the judges.[25]

The Minnesota Supreme Court also addressed claims that the actions of United Church constituted a recognition of the superior rights of the Oftedal Trustees to the control of the Augsburg Seminary corporation, by providing in part as follows:

Great stress is also laid upon the fact that until 1896 the United Church never asserted, or attempted to exercise, the right to elect the trustees of the seminary, but, on the contrary admitted by their conduct that they had no such power.

This amounts to nothing more than evidence of their views of the law at that time. There is nothing in it that would estop the United Church from afterwards asserting and exercising the right to elect trustees, if they in fact possessed the legal power to do so. . . .[26]

The Minnesota Supreme Court identified the legal burden which the Competing Trustees were required to carry in the action before the Court, by providing in part as follows:

The relators were elected by the conference of the United Church.

Therefore it is incumbent on them to show that the members of that conference, either individually or collectively, were the members of the corporation.

They were certainly not made such by the original articles of the incorporation.

As these articles were originally adopted, the five incorporators were the only members, in whom exclusively was vested the power to amend the articles and admit new members.[27]

The Minnesota Supreme Court did identify that the United Church was a continuation of the unincorporated Conference, by providing in part as follows:

It also appears clear to us, as a legal proposition, that the change of name and other minor changes in the constitution do not destroy the identity of the conference and the United Church, that the latter is but the continuation of the former, and that whatever rights, if any, the old conference had to the control of the seminary and its property are now vested in the United Church.[28]

However, the Minnesota Supreme Court declined to determine whether the United Church had any claims against the property of Augsburg Seminary:

It is neither appropriate nor necessary at this time to determine whether the [United] church has any such rights recognized by the law, or, if so, what the proper remedy would be.

But, if it has any such right of which it has been deprived, a court of equity is equal to every emergency, and its machinery and process are sufficiently flexible to meet it.[29]

The Hennepin County District Court had not made a determination as to the respective rights of the parties to the property of the Augsburg Seminary corporation.

It had merely determined that the Competing Trustees were not in charge of the corporation.

The Minnesota Supreme Court suggested that a court of equity was the proper forum for determining property disputes of this type.

A court of equity administers and decides controversies in accordance with the rules, principles, and precedents of equity, and follows the forms and procedures of Chancery.[30]

“Chancery’s jurisdiction was complementary to that of the courts of common law –

it sought to do justice in cases for which there was no adequate remedy at common law. It had originated in the petition, not the writ, of the party who felt aggrieved to the Lord Chancellor as ‘keeper of the King’s conscience.’”[31]

Historically, courts of equity were administered by the king’s ecclesiastical officials, and courts of law were administered by the king’s judicial officers.

In contrast, a court of law is any judicial tribunal that administers the laws of the state or nation—a court that proceeds according to the course of the common law, and that is governed by its rules and principles.[32]

In Minnesota, the two types of courts have been combined into the jurisdiction of the local District Court.

The Minnesota Supreme Court remanded the case back to the Hennepin County District Court, and the Oftedal Trustees and the Friends of Augsburg rejoiced when the Supreme Court reversed the verdict of the District Court, and declared that Nils C. Brun and the Competing Trustees elected by the United Church had no right to control Augsburg Seminary.[33]

The Minnesota Supreme Court’s decision was issued while the Oftedal Trustees and the Friends of Augsburg—who had just recently organized a new church body known as the Lutheran Free Church—were attending the 1898 annual convention of the newly formed society in Minneapolis, at the same time that the convention of the United Church was being held in St. Paul.[34]

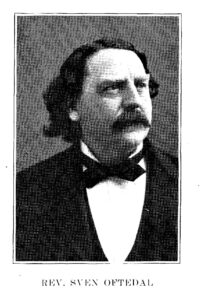

However, Sven Oftedal was on vacation in Europe when the Minnesota Supreme Court decision was issued.[35]

While the original incorporators of Augsburg Seminary were recognized as having control over the Augsburg Seminary corporation, it was not a complete victory for the Oftedal Trustees.

The Minnesota Supreme Court had declined to determine whether the United Church had any valid claim upon the assets of the Augsburg Seminary corporation.

Therefore, additional litigation on that issue was still possible, and the 1898 annual convention of the United Church authorized its officers to take further legal action if necessary.[36]

Notes

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Minnesota_Supreme_Court_Justices

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Minnesota_Supreme_Court_Justices

[3] State Ex Rel. Brun, et al v. Oftedal, et al, 72 Minn. 498, 75 N.W. 692 (1898). Nelson and Fevold, Lutheran Church Among Norwegian-Americans, 2:75, citing Nils C. Brun, and Others v. Sven Oftedal and Others, Minnesota Reports, LXXII (1898), 498-516.

[4] Minneapolis Tribune, July 15, 1898, page 3. Chrislock, From Fjord to Freeway, page 79.

[5] State Ex Rel. Brun, et al v. Oftedal, et al, 72 Minn. 498, 503, 75 N.W. 692, 693 (1898).

[6] Ibid., 693-694 (1898).

[7] Nelson and Fevold, Lutheran Church Among Norwegian-Americans, 2:75.

[8] Ibid, citing Nils C. Brun, and Others v. Sven Oftedal and Others, Minnesota Reports, LXXII (1898), pp. 499.500.

[9] State Ex Rel. Brun, et al v. Oftedal, et al, 72 Minn. 498, 503, 75 N.W. 692, 693 (1898).

[10] State Ex Rel. Brun, et al v. Oftedal, et al, 72 Minn. 498, 512, 75 N.W. 692, 697 (1898).

[11] State Ex Rel. Brun, et al v. Oftedal, et al, 72 Minn. 498, 75 N.W. 692 Minn. 1898, June 09, 1898.

[12] State Ex Rel. Brun, et al v. Oftedal, et al, 72 Minn. 498, 504, 75 N.W. 692, 694 (1898).

[13] Nelson and Fevold, Lutheran Church Among Norwegian-Americans, 2:75. State Ex Rel. Brun, et al v. Oftedal, et al, 72 Minn. 498, 511-512, 75 N.W. 692, 696-697 (1898).

[14] State Ex Rel. Brun, et al v. Oftedal, et al, 72 Minn. 498, 512, 75 N.W. 692, 697 (1898).

[15] State Ex Rel. Brun, et al v. Oftedal, et al, 72 Minn. 498, 509, 75 N.W. 692, 695 (1898).

[16] State Ex Rel. Brun, et al v. Oftedal, et al, 72 Minn. 498, 509, 75 N.W. 692, 696 (1898).

[17] State Ex Rel. Brun, et al v. Oftedal, et al, 72 Minn. 498, 509, 75 N.W. 695, 696 (1898).

[18] State Ex Rel. Brun, et al v. Oftedal, et al, 72 Minn. 498, 509-510, 75 N.W. 692, 696 (1898).

[19] State Ex Rel. Brun, et al v. Oftedal, et al, 72 Minn. 498, 502, 75 N.W. 692, 693 (1898).

[20] State Ex Rel. Brun, et al v. Oftedal, et al, 72 Minn. 498, 511, 75 N.W. 692, 696 (1898).

[21] State Ex Rel. Brun, et al v. Oftedal, et al, 72 Minn. 498, 511-512, 75 N.W. 692, 697 (1898).

[22] State Ex Rel. Brun, et al v. Oftedal, et al, 72 Minn. 498, 499-500, 75 N.W. 692, 692-693 (1898).

[23] State Ex Rel. Brun, et al v. Oftedal, et al, 72 Minn. 498, 502, 75 N.W. 692, 693 (1898).

[24] State Ex Rel. Brun, et al v. Oftedal, et al, 72 Minn. 498, 510, 75 N.W. 692, 696 (1898).

[25] State Ex Rel. Brun, et al v. Oftedal, et al, 72 Minn. 498, 510, 75 N.W. 692, 696 (1898).

[26] State Ex Rel. Brun, et al v. Oftedal, et al, 72 Minn. 498, 510, 75 N.W. 692, 696 (1898).

[27] State Ex Rel. Brun, et al v. Oftedal, et al, 72 Minn. 498, 512, 75 N.W. 692, 697 (1898).

[28] State Ex Rel. Brun, et al v. Oftedal, et al, 72 Minn. 498, 511, 75 N.W. 692, 696 (1898).

[29] State Ex Rel. Brun, et al v. Oftedal, et al, 72 Minn. 498, 511, 75 N.W. 692, 696 (1898).

[30] See Black’s Law Dictionary, 7th Edition, page 357.

[31] See Black’s Law Dictionary, 7th Edition, page 225, citing A.H. Manchester, Modern Legal History of England and Wales, 1750-1950 135-36 (1980).

[32] See Black’s Law Dictionary, 7th Edition, page 358.

[33] Helland, Georg Sverdrup, 160.

[34] Ibid. Nelson and Fevold, Lutheran Church Among Norwegian-Americans, 2:77.

[35] Ibid, 2:78.

[36] Chrislock, From Fjord to Freeway, page 80.

Copyright to the text 2019, Gary C. Dahle. All rights reserved.