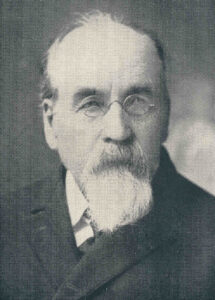

Reminiscences

of

Pastor Ole Paulson;

1907 Autobiography.

Chapter Seventeen

A translation from the Norwegian language into the English language.

Copyright © 2022 by Gary C. Dahle, all rights reserved.

In St. Louis

St. Louis was under military administration at this time. The entire city government was in the hands of the commanding general, who was General Rosecrans, for the time being. This was seen as necessary because of the large number of soldiers staying in the city at any given time. The military men of our times enthuse about the so-called Army canteen, in other words, the Army saloon. In those days, it was necessary to close the saloon to soldiers. General Rosecrans had issued a strict military order forbidding soldiers to visit saloons. If a saloonkeeper sold intoxicating drink to a soldier, he would lose his license and his saloon would be closed. The general did in fact enforce this order; there were numerous saloons that were shuttered.

For the three or four months that remained in the winter of 1863 and ’64, the company served in St. Louis. That consisted essentially of holding watch at a prison. It was not military prisoners we stood watch over, but offenders of all kinds.

The first day we began this service at the prison, we received our instructions. No one should be allowed to pass out of or into the prison without a pass. Only the prison personnel had free passage to and from the prison.

There was a large anteroom, with guards at the inner and outer doors. A person had to pass through there to come in or out. Two of the boys stood watch, one at each door. One of these was my own brother, Johannes Paulson.

He was at that time just a common soldier, but in some months he was promoted to captain of a negro regiment.

There came a bold young man up to the guards, with a thick book under his arm and a pen behind his ear. Another one followed him to the door and addressed him: “Mr. Secretary! Will you be so good as to speak to the general about my case, please?” “With great pleasure, sir,” answered the other. The secretary was let out, as one of the prison’s officials. Immediately afterward came the prison’s sergeant, on the run and short of breath, and asked the guards if such and such a person had been let out. “Yes, of course, we assumed that he was the prison secretary.” “You were duped. It was one of the prisoners, a serious offender, that you released. Now you yourselves will be arrested.” The guards were disarmed and put into the hole. I had command of the company at that time. I felt bad for the boys, who were entirely innocent. The fault lay with the unclear instructions. I wrote immediately to the general and presented the matter to him in the correct light. As a consequence, the boys were released on the spot.

The company had its quarters on the third floor of a large, old hotel. The room we got had been used as a ballroom. Here, the boys lay spread out on the floor, smoked, joked and chatted, sang ditties, and had a good time. For fun, they started to light their pipes with cartridges. A coal fire burned in the hearth.

Sergeant Graetch was going to be more daring than the others and lit his pipe with a cartridge that was already burning out. As he stood and put the lit strip of paper up to his pipe, the cartridge exploded right in his face. The sergeant fell on his back, as if he were shot. His beard, eyebrows, and hair were singed off. His face looked like a scalded pig. His pipe disappeared, as if it were shot right down into his belly. The strange thing was that he wasn’t blinded. The sergeant never wanted to hear about this episode.

The day after we arrived in St. Louis, our company received orders to escort the body of a major to his grave. It was seven miles out to the graveyard. As tired as we were after the summer’s exertions, we had to go. Still, there was some grumbling and dissatisfaction in the company. Military etiquette, however, does not allow for any deviations, one has to follow all orders precisely, no matter how plaguesome they might be. So, also, with the order to escort the body to the grave. It must take place inchingly slowly, at a pace that is called a death march. One’s weapon is carried upside down, right across the back. To march seven miles in this posture was not a bit fun. Some of the boys began to give up. I gave them permission to fall out of the line. When we came to the grave, not many were left in the company. The boys were grateful. Small kindnesses like that win their favor more than anything else does. An officer who has won the good will and favor of his soldiers can lead them through fire and water, if need be.

A Little “Reprimand”

Captain Baxter was a Yankee and a bit of an aristocrat militarily. One day, he invited me into his tent to give me a mild reminder about improprieties in my conduct!

“Lieutenant!” he said. “I find it necessary to remind you about what is unacceptable in your conduct toward the men in the company. You interact with them as if they were your equals. Horse around with them in the tents, sit together with them in confidential klatches. You must remember that you are an officer and in no way on equal footing with them. With such conduct, the soldiers lose respect for you and you, in turn, lose control.”

“Captain!” I said. “You are greatly mistaken. Before we joined the Army, they were all my equals. What I am now, these same men have made me. I feel myself now to be neither more nor less than they are, and intend to conduct myself accordingly. It is different when we engage in our duties. Then I am an officer and they are enlisted men. Then I demand respect and discipline. And I guarantee that I can exercise full control over them and lead them through fire, if required. Have you noticed, Captain, that the company does not obey me when I lead it?” “I cannot say that I have.” “I hope that you will never see it!” “All right. Have your will.”

Rolla, Missouri

In the late winter of 1864, the company received orders to go to Rolla, Missouri, to serve at the garrison there. There was a military base there with a prison, where Rebel prisoners were kept watch over.

Here, several companies of the our 9th Minnesota Regiment were gathered, and the regiment was expanded with the addition of 200 recruits from Minnesota.

I was selected to train these recruits in exercises.

Rolla was a small town about 100 miles to the southwest of St. Louis.

At the beginning of May, the regiment got orders to gather in St. Louis to go to Little Rock, Arkansas. It was the first time our regiment was gathered.

Early one morning, we came to St. Louis and marched through the city to a place where we were to have our camp.

Company H of the 9th marched in front of me and my company of recruits. Lieutenant Weissmann led Company H. The captain was sick, as usual.

The largest man in the company was a Swedish man by the name of Stor.[1] He had a position at the right flank, next to the commanding officer. One day, this lout had, one way or another, gotten a bit of something that had gone to his head, so that he conducted himself in an unseemly way in the ranks. The lieutenant addressed him, but Stor continued his bad behavior. Then the lieutenant got angry, grabbed Stor by the shoulder and shook him, shoved him into his place and said: “Keep your place, Sir!” Then the berserk lifted his weapon and hit the lieutenant over the head with the weapon. He thrust at Stor with his sword in the chest, to run him through, but luckily he hit the brass plate in his belt, otherwise he would have killed him on the spot. Now Stor threw his weapon aside and grabbed the lieutenant in his bear-like arms to crush him. However, a sergeant from the company came running, grabbed Stor’s knapsack, and hit him over the head with it so he fell on his face in the street. The lieutenant had fainted. The blow had struck him on the side of the head and torn his skin loose, so it hung over his ear. Stor was arrested and the lieutenant was put in the hospital.

This was the last service these two men did for Uncle Sam.

Stor lay in the guard house all summer, was never punished, and at last was released. The lieutenant lay a long time in the hospital, resigned, and came home.

Now I saw the situation for what it was.[2] The captain was sick and Lieutenant Weissmann was in the hospital. Therefore, I was again tasked with being alone with the company, as I had been continually when we had active duty. The captain spoke with me one day and said: “I feel truly sorry for you and feel compassion for you. Now I can see how things are turning out. You are charged now with being alone with the company this summer. As you know, I am sick and cannot go south with the company, and I do not want to resign, as I have decided to make the Army my home. When the war is over, I will apply for a position in the regular Army. Lieutenant Weissmann is disabled for the summer. He is scarcely likely to come back to the company. You are also not well and for that reason have good grounds to resign, if you want to. That is what I wanted to say: If you want to resign, I will help you. There are other more hale persons, who can fill the position and hold it for a time.”

On closer evaluation of the situation, I came to the conclusion that I would follow the captain’s advice; I sought and received a discharge.

[1] “Stor” was an apt surname for this man; it means “big” in Norwegian and in Swedish.

[2] Paulson uses an idiom here, literally “Now I saw what [time] the clock had struck,” whose meaning is as given in the translation: to recognize the reality of the situation.

Translation of chapter from the Norwegian language into the English language, and preparation of footnotes, by Denise Logeland.