Reminiscences

of

Pastor Ole Paulson;

1907 Autobiography.

Chapter Twenty-one

A translation from the Norwegian language into the English language.

Copyright © 2022 by Gary C. Dahle, all rights reserved.

About Augsburg

I have been called the grandfather of Augsburg. I have probably been given this addition to my otherwise fairly good name because I was, in a way, the means by which Augsburg Seminary came to Minneapolis.

Augsburg’s history has been told so often that it would seem superfluous to say anything here about the matter. Still, I think I ought to have a chapter in this book about Augsburg’s history in Minneapolis.

Judge Vanderburgh was, so to speak, my neighbor in Minneapolis.

We became well acquainted and good friends right after I arrived in the city. One day when we met, he brought up the topic of the city’s future. He said:

“Minneapolis will, without a doubt, become a large city in the near future, and we should do all that we can to help it progress. My opinion is that Minneapolis ought to be made into the headquarters for the Scandinavians in the Northwest. There is nothing that helps a city advance as much as good schools do. We ought to get a Scandinavian institution of higher education in the city.”

I agreed, and was glad for the judge’s positive assessment and thoughts about us Scandinavians. In the moment, I didn’t know how a Scandinavian institution of higher learning could be established in Minneapolis. This conversation was had as early as 1869.

Already that same autumn, Augsburg was established and located in Marshall, Wisconsin.

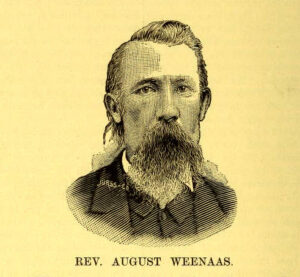

Professor August Weenaas was then the Norwegian department’s theological professor at the Augustana Seminary in Paxton, Illinois.

Without any synod decision about it, the professor had dismantled his household in Paxton and was moving westward when we arrived at the synod meeting in Moline in June 1869, not knowing with any certainty where he would land with his school. There had been some provisional discussions about moving from Paxton, but nothing had been decided yet about where we should actually go with our school. Now it was hard to know what to do. It was decided in the Norwegian department’s meeting in Moline to buy the old academy building in Marshall, Wisconsin, and to move the school there. Marshall was no place for us, but one had to grasp at something in a time of need. Professor Weenaas now moved to Marshall and opened the school there at the beginning of the school year in the fall of 1869. The school at that time consisted of one professor, August Weenaas, one teacher, and 19 students.

In the summer of 1870, the Scandinavian Augustana Synod held its annual meeting in Andover, Illinois. The Norwegian department had already discussed, at a meeting the previous fall in Racine, Wisconsin, separating from the Swedish brothers. So we came to the meeting in Andover prepared to take this important step.

It was resolved that the divorce would take place, although not unanimously, as there were two pastors, Ole Andrewson

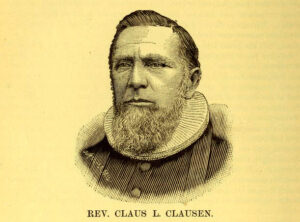

and Andreas Aslaksen Scheie, who protested the decision by not resigning themselves from the synod. A temporary organization was then formed under the name “the Norwegian Augustana Synod,” with temporary officers. It was also decided there to defer a permanent organization until people had met with Pastors Clausen

and Gjeldaker and their congregations, which had left the Norwegian Synod, about uniting, so that these brethren could gain admission and join in the permanent organization, presuming that they were in agreement about the teachings. It was also decided that if agreement could not be reached, the permanent organization would be carried out, either there, where the meeting to unite was held, St. Ansgar, Iowa, or at some other place in the vicinity.

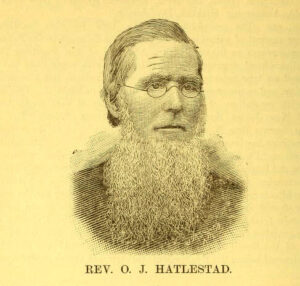

When Pastor Ole Hatlestad

recounts the actual act of division, the wording was decided as he says. But afterward, in our own meeting at the same location, it was decided as recounted by me above. The Norwegian Augustana Synod was not permanently organized in Andover. Those who say the opposite are wrong.

A conference was held in St. Ansgar at the home of pastor Claus Lauritz Clausen from the 10th to the 16th of August, 1870. People discussed the teachings and came to full agreement so that a synod could be founded, and it was decided thus.

But now there came a stumbling block that got in the way. People were not in agreement about what kind of a communion it would be. Some wanted to have it constituted as a full-fledged synod, with the name “the Norwegian Augustana Synod.”

Clausen and his friends wanted to have a conference without a fixed synod organization.

Professor Weenaas had gone over to Clausen’s conception.

The pastors would form a sort of pastoral conference, the meetings of which congregations would have access to without formally belonging to this conference. Finally, after much debate, this idea was voted in “on a trial basis.”

Hatlestad alone voted against this resolution and separated himself from us. “I am too old to go along with a church by trial,” he said. Therewith ended that matter. We agreed on the name: “The Conference for the Norwegian-Danish Evangelical Lutheran Church in America.”

The “trial” ended at the next conference meeting, in Minneapolis the summer of 1871, where a new constitution was voted on, a full-fledged synod concept, without changing the name, which people had already learned to love.

At the Extraordinary[1] Meeting

In Madison, Wisconsin, the same year, a committee of three members was named to research where the best conditions were for placing a seminary. At this Extraordinary Meeting in Madison, our accounts with the Norwegian Augustana Synod were settled and closed. The conference retained the professor and the students, Augustana got the building.

So it was now necessary to find a permanent place for Augsburg Seminary. It is noted here that we kept the name Augsburg Seminary.

As mentioned, a committee of three members was selected for this purpose: Professor August Weenaas for Wisconsin, Pastor Claus Clausen for Iowa, and Pastor Ole Paulson for Minnesota.

When I came home from the remarkable meeting in Madison, I went to work to see what Minneapolis could offer us in the way of inducements. The other two did nothing, for the reason that Minneapolis took the wind out of their sails.[2] I went immediately to my friend Judge Vanderburgh and reminded him of what he had once said.

He remembered it and was still of the same opinion. I presented to him now the prospect of getting a theological teaching institution to the city, if it would give us an inducement of some significance. He was enthusiastic and wanted to help in whatever way he could. He called a meeting of the leading men in the city.

The meeting was held in the judge’s office. Editor William T. Rambusch[3] was secretary at the meeting. When I had presented the matter the best that I could, it was unanimously resolved to invite Augsburg Seminary to be located in Minneapolis, with a promise of obtaining a parcel and, in addition, monetary help for the construction of a building.

Summer 1871

The conference held its annual meeting at the new Trinity Church in Minneapolis. At this meeting, it would be decided where the seminary would be located.

The author, who was a member of the committee, reported what he had undertaken and with this backgound, spoke in favor of locating the school in Minneapolis, and requested of the meeting’s members that they take a look at the place where the seminary was intended to stand. The suggestion was unanimously adopted. It was no large band of people who now processed through Minneapolis out onto the prairie, where our “problem child” to be, Augsburg Seminary, was intended to stand. The whole group consisted of perhaps 30 men, 19 to 20 pastors and a number of delegates.

The annual meeting voted unanimously that Augsburg Seminary should be located in Minneapolis, Minnesota, on the condition that the city’s residents provided a lot to build on at the indicated location and a building costing at least 4,000 dollars. The Minneapolis delegation, together with the pastor, agreed to these conditions. In this manner, the matter was settled and closed.

A committee of three members was selected, namely: Pastor Ole Paulson, Andrew Taraldson,[4] and Aron Hendrik Edsten.

The building plan and drawing was delivered by Isak Davidsen Røsrud,[5] and he also did the woodworking for the building. The masonry and plastering were done by Andrew Sødren.[6]

The work of collecting money and keeping an eye on the workers, so that all was carried out as agreed, fell mainly to the committee’s foreman, who had his hands full with running around gathering money and with getting materials to the site until his feet were sore.

Amidst poverty and with all the struggles, the building was really just barely finished in time for Professor Weenaas to be able to move in at the beginning of the school year, on the 15th of September, 1872.

It was a big day for us when the building was dedicated. Speeches were given in both English and Norwegian in the seminary’s auditorium, and in the evening, there were speeches in the church as well as songs from a large choir, which Pastor Paulson had directed.

Professor Weenaas now moved into the new building with his little flock, 21 in number, of which 15 belonged to the preparatory and seven belonged to the theological department.

After the bitter experiences the school had in Marshall, it is nothing strange that Professor Weenaas rejoiced in his report to the annual meeting in Eau Claire in 1873.

Now there are no fewer than four Norwegian theological learning institutions in Minnesota, three in the Twin Cities and one in Red Wing. Augsburg was the first that ventured forth with a national educational institution for pastors.

When we now look back and regard the actual conditions and poverty of that time, we must marvel at our great boldness, which dared to embark on such an undertaking. When the work was to begin in the autumn of 1871, the committee did not have one cent in the treasury.

The foundation had to be laid that fall, so that as early as possible in the coming year the lumber work could begin. I talked with an old American about whether it was necessary to dig deep for the foundation. He gave me the advice to place the foundation above ground, for he said the earth is just as hard above as it is a couple of feet farther down.

If you cannot go below the frost line, it doesn’t help to go a couple of feet. I realized that I couldn’t start out with an expensive foundation. I borrowed 60 dollars from Miss Karen Danielson, now Mrs. K. Olsen, and laid the foundation above ground. What’s remarkable about this masonry is that after 34 years, there’s not a crack in either the foundation or in the wall that is laid on the foundation.

The section of the building that was put up a couple of years later, built on the bedrock, is also good, of course, but no better than the old part of the building. The fact is that the bedrock, eight feet below, protects the foundation against frost, so that it doesn’t have the force to crack the wall.

The Lord steered things well for us. We went blindly ahead with the belief that it would work out and it did work out. The building cost us 6,000 dollars and there was not so very much debt when it was finished. The majority was given by the citizens of Minneapolis as private gifts. If a building such as this were to be put up now, it would cost twice as much. In those days, one could build relatively cheaply. Lumber was cheap and labor likewise.

[1] I’ve understood “extraordinary,” in this case, to mean a meeting that was outside of or beyond the normally scheduled meetings, such as annual meetings, held by the synod. But it’s possible that Paulson meant “extraordinary” in the sense of “remarkable.” He uses the word “underlig” a couple of paragraphs later, which does mean “remarkable” or “strange” or (in a more archaic and Biblical way) “wonderful.”

[2] Paulson writes, literally, that “Minneapolis took the wind out of them.”

[3] Paulson identifies this person as “Editor Rambusch,” using only the title and surname. He appears to mean William T. Rambusch, the publisher of Nordisk Folkeblad, a Norwegian-Danish-language weekly paper. Carl G. O. Hansen, in his history of the city titled My Minneapolis, identifies “W. T. Rambusch” as the first Scandinavian banker in Minneapolis, whose building housed Nordisk Folkeblad. In addition to appearing on the paper’s masthead as publisher during the era Paulson is writing about here (1870–71), Rambusch’s name appears on a number of advertisements that name him as a banker; as the vice-consul for Norway, Sweden, and Denmark; and as the owner of businesses including an immigration agency.

[4] Paulson names “A. Taraldson,” who is probably Andrew Taraldsen (the name appears with a number of spelling variations). He was active as a member of Trinity congregation during Paulson’s time there, including as a choir member and leader of hymns. See the 50th anniversary book of the Trinity congregation, page 65, digitized here: https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=PNYvAQAAMAAJ&pg=GBS.PA64&hl=en

The same Taraldsen might have been among the early Norwegian merchants (grocer) in Minneapolis. He appears in the 1880 census, living with his wife and family on 3rd St. in Minneapolis.

[5] Paulson writes “I. D. Røsrud.” Isak Davidsen Røsrud’s full name appears in an article he submitted to Nordisk Folkeblad, published September 8, 1869 (see page 8, bottom of column 6 and top of column 7). In the article, he corrects misinformation about a companion with whom he emigrated from Eidskog in the Hedemark region of Norway: https://newspapers.mnhs.org/jsp/PsImageViewer.jsp?doc_id=be0325fb-0b6e-4274-b276-7c9852567f93%2Fmnhi0031%2F1EMKA356%2F69090801

Also in Nordisk Folkeblad, Røsrud submitted and signed a letter, published February 15, 1871 (see page 8, bottom of column 3) in which he corrects mistaken rumors about the financial standing of the Trinity Church. Røsrud signed the letter as secretary of the congregation:

[6] Here, Paulson writes “A. Sødren.” It is probably the same Andrew Sodren who appears in the 1880 census as a 40-year-old “stone and brick mason.” He had by that time moved to Willmar, Minnesota, with his wife, Clara (Andrew at bottom of page 28, Clara at top of page 29): https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GYBK-2J?i=27&cc=1417683&personaUrl=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AMZ9D-3FB

They appear to have been married (Andrew A. Sodren and Clarissa Page) in Hennepin County in 1875: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939K-RPSX-5J?i=1220&cc=1803974&personaUrl=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AQJGY-Y5Y5

Translation of chapter from the Norwegian language into the English language, and preparation of footnotes, by Denise Logeland.