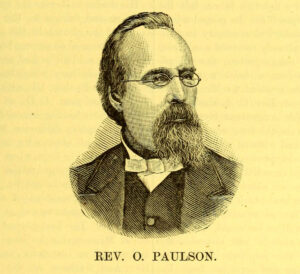

Reminiscences

of

Pastor Ole Paulson;

1907 Autobiography.

Chapter Twenty

A translation from the Norwegian language into the English language.

Copyright © 2022 by Gary C. Dahle, all rights reserved.

To Minneapolis

The Scandinavian Augustana Synod held its annual meeting that year at East Union Congregation,[1] Carver County, Minnesota. It was an abundantly attended meeting. I had come to the meeting with the thought of being ordained, but found that the congregation that had called me had had troubles and had dissolved. The original congregation was Scandinavian. A rift developed between the nationalities, with the result that the Norwegians and Swedes each went their own way and organized themselves into congregations.

The Norwegians had come together, and had signed their names and issued a sort of call letter to me.

The letter of call was so incomplete that I could not accept it. Now the question became what I could do in order to be ordained. Some were of the opinion that I could not be ordained without a call from a congregation. Others believed that the synod had the right to call and ordain mission pastors. The great majority at the meeting were of that opinion.

In addition, I had, in fact, been called to Minneapolis. One should also take this into account. So it was decided that candidate Ole Paulson was called as a mission pastor to Omaha, Nebraska, with the explicit understanding that he would first spend some time working in Minneapolis. If he should find that he ought to continue his work there, he had the freedom to do so.

With that call, I was then ordained by the synod president, Professor Tufve Nilsson Hasselquist, on the 14th of June, 1868. The ordination certificate is signed by T. N. Hasselquist, president of the Augustana Synod, and Pastor Jonas Swenson, secretary.

Now this goal had also been reached. I was now a pastor, in such a manner that even the very high-church Episcopalians would acknowledge my ordination, because I am ordained by a pastor, who was himself ordained by a bishop.

On the 4th of July, 1868, I came to Minneapolis and was met at the depot by Mr. Eberhard Titterud,[2] who at that time was one of the leaders of the congregation that I would try to gather and serve. He took me with him home to his house. Back then, there were few Scandinavians who owned houses in the city. I think there were scarcely more than a half a score of Scandinavian homes in Minneapolis; the few that existed were both small and humble.

Mr. Titterud had his shoemaker’s workshop on Washington Avenue, at the point where the railroad crossed the avenue. The family lived above the workshop. Aron Henrik Edsten[3] had a little house on 12th Avenue between Third Street and Washington Avenue. In addition, there were a few others who had the wherewithall to have their own roofs over their heads. The number of inhabitants in the city at that time was perhaps 15,000.

Trinity Congregation

I found upon my arrival in Minneapolis that there was both “seed ground and summer sun enough” in Minneapolis. One didn’t need to be any kind of prophet to see and understand that the city would grow to be large over time, and that the Norwegian population would keep pace with the city’s development. I realized immediately that I did not need to travel to Omaha to find a mission field and more than enough to do. The congregation in Minneapolis did not yet have a name, only a list of members’ names. In great haste, it had built a small house for gatherings on Mr. Edsten’s lot on 12th Avenue. It was not plastered or furnished. The whole thing had been built on credit and there wasn’t one cent in the treasury. The roster showed 65 male members.

The first thing to do was to gather the people into an organized congregation. This was not so easily done. In a thorough undertaking, I found only 42 adults, women and men, who wanted to join the congregation. The majority of those who were on the roster of names were young, unmarried men, and many of them had already left the city. The congregation was then organized and the constitution adopted, under the name “the Norwegian-Danish Evangelical Lutheran Trinity Congregation of Minneapolis, Minnesota.” An awkwardly long name, but in daily speech it was shortened to “the Trinity Congregation.”

As indicated earlier, I had my church upbringing among the Swedes, and was very much against the practices used in Norwegian congregations, especially the pastor’s vestments, the liturgy before the altar, and absolution by the laying on of hands. We adopted, however, a way of conducting the absolution that I agreed to, a way involving question and answer together with the laying on of hands.

The liturgy issue was shelved for the time being. As far as vestments went, I fought well and in manly fashion against the “long dress.”[4] I thought it was so inhumanly old-fashioned, undemocratic, and ugly, that I could not imagine how sensible people could demand that a pastor should be burdened with such a monstrosity.

However, I had the entire congregation against me and was at the mercy of their power. I read Walter’s Free Church regarding the ceremonies of the church. Walter says that each congregation ought to have its own vestments hanging in the sacristy for use by the pastor who presides over services. Here is a solution, I thought. At the next meeting, when the matter came up for discussion, I conveyed what is said by Walter and added:

“If the congregation purchases vestments, I will wear them. It costs approximately 40 dollars. My cashbox is empty, so that I cannot take on the expense of such costly garments.”

It was unanimously decided not to purchase vestments. And therewith ended the conflict over the long dress.

I continued my work as pastor for a whole year or more, without this frock. But it was not entirely quiet. When strangers came to the city, they wanted to know, was there a Norwegian Lutheran church in the city? Yes, of course.

Was there a pastor? One couldn’t know for certain and thought perhaps that the sexton did the preaching. In reality, we had no sexton; I led the hymns myself and read the so-called sexton’s prayer. So I was both sexton and pastor.

Newcomers couldn’t make sense of it. The congregation wanted to have a “real” pastor with all of the pastorly appurtenances, gown and collar. People went about quietly collecting money for a frock and ordered it from a tailor, who at that time belonged to the congregation.

One day, as I passed the tailor’s workshop, I was called in. I asked the tailor what he wanted.

“To take your measurements for a coat.”

I brightened, looked at the threadbare one I had on, and thought:

“Now you’ll see, your friends have seen your worn out garments and have had pity on you and want to give you a new coat.”

But when I saw that the measuring tape went all the way to the floor, I asked:

“What kind of coat is this going to be?”

Then he smiled roguishly and said:

“So you don’t know that you’re going to have a pastor’s frock?”

“No.” “Yes, Father, now you’re going to have a pastor’s frock!”

I think I became a bit long in the face, but I said nothing.

Now we had a frock, but not a collar.

Where would we get that from? In those days, it was easier to get hold of a millstone around one’s neck than to get hold of a pastor’s collar. There was, however, a woman in the congregation who thought she could make one. She did, indeed, make a collar, but it was ugly.

Now people had a pastor with all the bells and whistles; now no one could say any longer that the sexton was giving the sermons. But now people said that in the little church on 12th Avenue, there was an old pastor from the state church[5] who had a pastor’s frock and even said the liturgy before the altar!

In this way, I came to use the Norwegian pastors’ vestments. It’s not good to fight the will of the people.

The Church Grew Too Small

The little crate that we had for a church was soon too small; it couldn’t hold the people who came to listen. Now it was hard to know what to do.[6] One needed a fairly roomy church to have seating for the many who sought God’s house.

First, we needed to make arrangements for a lot; it cost money and the cashbox was empty. I went to a real estate dealer and bought a lot on the corner of 10th Avenue and 4th Street.

The location was especially good and the lot was large. The congregation now purchased 100 feet of my lot, and of course got the corner for the same price that I had paid, though the corner is of greater value than the rest of the lot.

Now the congregation decided to go ahead with the building of a large church, 40 by 80.[7] We were in debt for our little crate of a building. In essence, we had to move ahead with building a new church in order to pay the debt on the old one.

The new church was large, given the circumstances, but very simple and very inexpensively built. It was entirely built of wood and took a great quantity of lumber. Back then, wood was cheap. The main thing with our new church was that it be inexpensive and roomy. Even so, it was not too big. It was packed two times every Sunday. We also had a large and good Sunday school.

The congregation, however, did not come out of the church construction without debt.

The Pastor’s Pay

A couple of words about this plaguesome subject. When I accepted the call that the congregation extended to me, the salary was set at 250 dollars for a full year, without any discussion of anything more.

In the winter, I would serve the congregation from Carver every other Sunday. I was, namely, as discussed earlier, employed as a teacher together with Pastor Andrew Jackson at the St. Ansgar Academy.

In the summer, I would live in Minneapolis and provide the congregation there with regular services every Sunday.

This agreement held for just one year, as I built a house for myself in Minneapolis and took residence there already in the autumn of 1869. But the salary agreement remained the same, a firm 250 dollars.

There was, however, incidental income from the baptisms of children and from wedding ceremonies. From baptisms, there was not so little that came in. It was the custom to have many sponsors, who all made offerings in addition to what the father himself paid. There were often 10 to 12 dollars coming in on this occasion.

There were frequent burials, but I was so pious that I did not accept payment for burials. I could not have kept life in my body with this income, if I had not had some resources of my own.

There were six offerings a year for the congregation’s treasury, but none for the pastor.

Things went along in this rhythm for the first four years that I was in Minneapolis.

The last two years, all arrangements regarding a fixed salary were removed. At an annual meeting, where the pastor’s salary was discussed, a suggestion was put forward that two of the offerings should go directly to the pastor.

The suggestion was supported. I took the floor and said:

“Let us erase all resolutions about a set salary, and let me receive the six offerings, and then as much as the people in their goodness are pleased to give.”

This won support. People said:

“If the pastor dares to risk it, then certainly we dare to, for then we have no other obligation than what we give of our free will.”

I declared that I would try it. That year, I received 200 dollars more than I had ever received earlier. For now, each and every one of them thought that the pastor ought to have something to live on, and so they came with their gifts to the treasurer.

When everything was fixed in place, no one thought about the pastor and his family; the amount that they would live on was set—250 dollars as a set salary. This payment arrangement was so set, that there was always an under balance at the annual meetings.

Now, one feels sorry for a pastor, for example in Minneapolis, with a salary of 600 dollars a year and compensation for renting a home. I had a set 250 dollars for the first four years I was in Minneapolis, and for the last two years no set amount, and paid for my own house.

It is worth noting, however, that all things are more expensive now than they were in those days. Back then, we bought good wood for one dollar a load. Renting a house was cheap. I would venture that it was one-third less expensive to live then than it is now.

I must say, however, as a pastor once said:

“It is not easy to be a pastor.”

“It’s certainly no easy thing to be a sexton, either,”

answered the other, who had been a sexton.

[1] In coming to this synod meeting in East Union, Paulson was coming to his home church, the one where he had been a congregation member and teacher for St. Ansgar’s Academy.

[2] Eberhard (E. M.) Titterud was the first person of Norwegian ethnicity to open a business in Minneapolis, a shoemaker’s shop in 1865, according to an article in Minnesota Stats Tidning (Minnesota State Times) on May 10, 1877 (see article on page one, columns 3–6):

Furniture maker A. H. Edsten (see next footnote) is also named in the article, which describes the growth of the Scandinavian population in Minneapolis and names early professional and business owners. Both men appear again in a similar article in the silver anniversary issue of the Minneapolis Journal on November 26, 1903 (see page 46, far-right column): https://newspapers.mnhs.org/jsp/PsImageViewer.jsp?doc_id=4b0d4236-188b-40ad-be89-7fd727b9dc91%2Fmnhi0031%2F1DFY7Q5A%2F03112601

[3] Paulson writes “A. H. Edsten.” Edsten’s obituary gives his full name as “Aron Hendrik Edsten” and describes him as a founder of the Trinity congregation, a trustee of Augsburg Seminary, and the owner of a furniture store at Third Avenue and Washington Avenue. See the Minneapolis Morning Tribune on March 7, 1917 (top of page 10): https://newspapers.mnhs.org/jsp/PsImageViewer.jsp?doc_id=addabf07-f848-43e3-a488-2782562f220d%2Fmnhi0005%2F1DFC5G5B%2F17030701

[4] Paulson uses the Norwegian word kjole, which in the present day is usually translated as “dress.” In Paulson’s day, it could mean a woman’s dress, or a man’s long coat, an academic’s gown, or a pastor’s vestments. In this section of the book, I’ve translated the word several different ways because Paulson is playing with the word and its multiple meanings to make fun of the long “dress” that pastors wore. His anecdote about his encounter with the tailor also hangs on the potential for misunderstanding due to the word’s multiple meanings. If Paulson had understood immediately that it was a long pastor’s frock he was getting, rather than a coat, he wouldn’t have been so happy.

[5] Paulson is referring here to the State Church of Norway, which would have been familiar to his readers. They would have understood what Paulson is saying between the lines. He’s making indirect reference to the state church’s formality—its “high church” character compared with many “low church” Norwegian-American Lutheran congregations—and he’s letting readers know that he wasn’t comfortable being mistaken for a state-church type of pastor. Norway’s state church existed from approximately 1030 to 2012, and began as part of the Catholic Church. It became Lutheran in 1537, following Martin Luther’s break-away reformation movement. In 2012, Norway’s parliament amended the country’s constitution so that the Lutheran church in Norway is no longer part of the state.

[6] Paulson uses an idiom here, “Nå ble gode råd dyr” (using modern spelling), which means literally “Now good advice was dear” or “expensive” or “precious.” The meaning is that it was hard to know what to do because good advice was hard to come by, a solution was hard to come up with.

[7] Paulson doesn’t give a unit of measure here, but he must mean feet, given the lot size.

Translation of chapter from the Norwegian language into the English language, and preparation of footnotes, by Denise Logeland.