Reminiscences

of

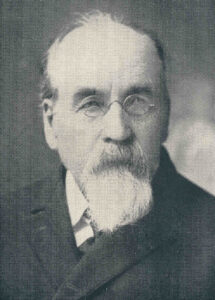

Pastor Ole Paulson;

1907 Autobiography.

Chapter Five

A translation from the Norwegian language into the English language.

Copyright © 2022 by Gary C. Dahle, all rights reserved.

To Iowa

In 1852, the majority of Wisconsin was an unoccupied wilderness, Iowa as well; Minnesota was desolate and empty, Kansas and Nebraska were just empty prairies, where the red man[1] and wild animals dwelled. The Dakotas were known only to the buffalo hunters and Red River half-breeds.[2] And what there was farther to the west, almost no one had knowledge of. One thought only about what opportunities there were for a bold young man to advance himself.

There are thousands of our countrymen who came here poor, in debt for their passage over, but whom the West has made nearly into millionaires and powerful, well-to-do people.

In the spring of 1852, I came back from Michigan to Muskego without having earned so much as my fare from Manistee to Milwaukee. We had the misfortune that, in the middle of the winter, something in the steam-powered machinery at the mill where we worked broke irreparably. The entire work force at that big sawmill was laid off for the rest of the winter. What little we had earned went to board and lodging for the remainder of the winter. For in those days, that part of Michigan was cut off from the rest of the world in winter, so that no one could come or go. Lake Michigan was frozen and there was no railroad. It wasn’t possible to repair the mill until shipping traffic began again.

There were some 30 of us men who lost our whole winter’s earnings.

A fairly active out-migration had begun from Muskego to Iowa and Minnesota. Those who already had gone west sent back glittering reports about the grand prospects in the West. “Only now has one found America,” it was said. This made the emigration fever pretty strong. For a time, it looked as if everyone would sell out and go. There was also some wisdom in selling, for the Germans had come in and they were more than willing to buy and pay relatively good prices. The Germans are not so particular about the land if it’s not the very best. Woods and brush don’t scare a German. The Germans are hard-working people and capable farmers. With hard work, they get the wasteland to bloom like a rose. One can hardly find land less attractive or more uninviting than Carver County in Minnesota was, before it was settled. Vast forests and brush in addition to ugly sloughs and bogs. In the turn of a hand, the entire county was settled by Germans. Now the land is cultivated and nicely built up. No finer farms are found in the state. The land itself was good and fertile, but what a job it was to make it into what it is now!

In the month of June, two families were going to go to Iowa, namely Amond Leidahl and John Waa. With my savings, I had bought a pair of steers, for which I paid 30 dollars. The oxen were two years old. I had farming in mind.

I decided to follow these two families. John Waa and his kindly wife, Signe, had promised that if I wanted to follow along with them, food on the trip would cost me nothing. I accepted their offer and joined them, as mentioned. The Waa folks were childless, but there was a young man with them named Knut Veseth, a brother of Signe Waa. We immediately became good companions and had a pretty good time on the trip. The means of conveyance was an ox cart. We had only one wagon. Obviously, we had to walk most of the way. Our route went through Skoponong,[3] Koshkonong, Madison, Blue Mounds, and Prairie Du Chien to Decorah, which at that time was in its infancy. It had only a few small houses.

Bitten by a Rattlesnake

On the prairie, some miles from Dodgeville, Wisconsin, I had the misfortune to be bitten on the sole of my foot by a poisonous rattlesnake. There were several of us young people in the traveling company. Most walked barefoot on a warm and sunny day. I pulled off my boots and stockings and was going to do likewise. When I took off running to separate our animals from some others that were out on the prairie grazing, I felt that something struck me on the foot. Since I didn’t feel any pain in connection with it, I didn’t give it any further thought and continued to run several more steps, until I heard the beast rattle. Frightened, I looked at my foot and became aware that blood was running from four holes in the sole of my foot. The rattlesnake has a relatively broad, large head with strong jaws and four curved fangs. The animal had gotten a good strike on me. It had bitten itself fast into me while my foot was off the ground. I almost think it must have hit the blood vessel that goes to the big toe. At any rate, the wound was in the right place.

I was scared nearly to death. A terrible fear comes with being bitten by the frightening beast.

I ran to the wagons and raised the alarm. The group was just as struck with fear as I was. What recourse should one turn to? Life is dear! No one knew what to do. I myself had heard that if one could immediately cut away the area where the bite was, it would help. I asked the group if anyone had a shaving razor. John Waa had one. Bring it right away! He brought the blade. I tried to make the cut myself, but shook so that I couldn’t. My companion Knut came to my aid, resolutely took the bitten flesh between his fingers, made a cut, and tossed the piece of flesh into the grass.

There was another remedy I had heard talked about. One should kill the snake, skin it, and lay a piece of the snakeskin on the wound. My friend went to look and see if he could find the snake. Yes, sure enough, there it lay, curled up, ready to strike again if anyone came near enough. It took just a second before Knut came back with the snakeskin and laid it neatly over the wound. There was one more remedy people knew of. It would help to drink whisky! But who had anything like that out here in the wilderness? Of course, John Waa had camphor liquor. Oh, let me have a swig of it! He brought the flask and I took a good swig of the horrible stuff; but anything tasted good that could rescue me. Then we wound a bandage around the foot and tied it firmly. Now all good advice had been exhausted, so it was only to wait for the results. After this treatment, I felt so well that I wanted to get up and go to the wagon, where they had made me a bed to lie on. During the operation, I sat on the ground. When I got up on my feet, everything immediately went black and I fell in a faint. After a time, I came to and people carried me to the wagon. When I had lain for a couple of hours or so, I felt so good that I wanted to get down from the wagon. When I got on my feet, I again fainted, as I had the time before, so that people once again had to lift me up into the wagon.

After a time, a man came and said that five miles[4] away, on the road we were going to travel, there lived a doctor. He believed it would be best to go and get him. One of the group threw himself onto a horse and rode away to get the doctor. The doctor arrived around midnight. When he saw what we had done, he scolded us for our foolishness, that we had maimed the foot. He tore off the bandages, washed the wound, and poured medicine into it. He also gave me some drops. When he had treated me, he went off and laid down in one of the wagons. I was greatly tired out and fell into a deep sleep. The doctor also slept. In the morning, when he returned to me, he found that the wound had been bleeding all throughout the night. Now the blood was so thin that the bandages couldn’t stanch the bleeding. He didn’t have with him the instruments necessary to stop the blood from flowing. He left and instructed us to drive after him as fast as we could. When we arrived at the place where he lived, he would come and stop the bleeding. We arrived at his house around midday. He was away for the time being and would not come home again before the late afternoon. Now he came with his gimlets and forceps, dug into the wound, and got ahold of the artery that had been cut and tied it off with a thread. Did it hurt? I should say so. It took two men to hold me while the brute dug into the wound with his instruments. But the main thing was that the bleeding stopped.

In a couple of days, I became very ill and the leg swelled up to an unnatural size. Nonetheless, I became well again. In a couple of weeks, I was quite healthy. The accident was a costly lesson for me. I couldn’t help but imagine my death and I was not prepared to die. Oh, how afraid I was to enter into the dark and hopeless eternity. There wasn’t the tiniest glimmer of light to be seen in the blackness of the grave. I didn’t want to die, as young and full of the joy of life as I was. If only I could be allowed to live, I would have given whatever it took. Ah, Death, how bitter is your sting for those who are ungodly. England’s wealthiest youth died recently in California. He cried out in anguish to the doctors who cared for him: “Save my life and you shall have all of my riches!” I had no riches, but if I had, I would have gladly given them all in order to live.

Signe Waa was a very kind and religious woman. Oh, how she wept and prayed for me, that I would be saved. I believe the Lord heard her prayer, if not exactly in the way she had imagined. Amond Leidahl was also a very earnest Haugean. But his religion did not appeal to me. He was altogether too sour, I thought.

One time along the way, he nearly got a beating, had it not been for my companion and me. Near Koshkonong, we met a young Norwegian farmer, who came driving with a load of wheat. After we had exchanged some words about this and that, Leidahl asked him how it stood with his poor soul, whether he had reconciled with his God, et cetera. The man became enraged. He stood with the whip in his hand, as if he were going to lash the poor old wretch. “Come,” I said to my friend. “Let’s go over and scare the stranger.” We walked close up to him and looked him straight in the eye. He said: “I could have quite a bit to say here, but it’s not good to get drawn into a dispute in a strange place among unknown people!” And with that, he sprang up onto his wagon, gave a snap of his whip to the horses, and disappeared. As long as we talked about the market and wheat prices, the man was mild-mannered and communicative. He said that he was driving the wheat to the nearest train station, which was Palmyra,[5] and got a good price for his wheat, 35 cents per bushel. It was no longer as it had been before, that one had to drive all the way to Milwaukee, 100 miles, and sell the wheat for 25 cents a bushel.

It fell upon Old Amond, as his particular Christian duty, to speak a word of warning and admonishment to whomever he met. Sometimes, he came out with it quite clumsily and unexpectedly. He didn’t take into account the effect his message could have. The main thing for him was to unburden his conscience. This time, it didn’t go well. The man became offended and angry.

Amond was, in a way, the leader for our company of travelers and decided what was Christian in manner. He decided that we should rest over the sabbath and keep it holy. He was, in a way, our house pastor. Sunday forenoons, he held a worship service for us, read a sermon, sang, and said prayers. Then we young ones didn’t dare do anything but be intensely devout, even though, unfortunately, our piety was not great. We had little respect for the old man. He was far too sour and peevish, we thought. On occasion, Knut and I provoked him to anger, which is to our shame. We two were not pious, and so we found it entertaining to irk him until he was angry. He wanted to be the boss over the rest of us in everything. When it came to religion, he got no resistance because the old man was the master in our eyes, except when he was wrathful. But he wanted to boss us in all things. In that regard, we thought we sometimes ought to speak against him. He did not tolerate it. Sometimes, we compelled him to give in. Then we were so satisfied. Old Leidahl is already long since dead. John Waa and his loving wife, Signe, long ago passed away. I hope they have both “died in the Lord.”

Without any further misfortune, we arrived happily in Decorah, the county seat for Winneshiek County, Iowa. To the east and the south of the town, there were already some fairly large Norwegian settlements. To the east is the well-known Washington Prairie, where Pastor Ulrik Vilhelm Koren has lived since he came to America in 1852. To the south is the Turkey River Settlement.

Northwest of Decorah is the Big Canoe Settlement. Amond Leidahl had this settlement in his sites and wanted to go there. I believe he had acquaintances there. We followed him there. Here Leidahl found land that he liked, whereupon he settled. We didn’t like the land in Big Canoe and went back to the Turkey River Settlement, where Waa had acquaintances who had settled there the previous year.

Here there was opportunity to get good, attractive land at the government price, 1.25 dollars per acre.

In those days, there was no homestead land to be had. The homestead law came many years later.[6] Now we were in a difficult position,[7] to know which land we should choose. The whole vast, beautiful prairie lay open before us, but we wanted woods and prairie in a single parcel. When we didn’t get that, we rejected it. Along the Turkey River, there was a belt of forest, which the first settlers had laid claim to, with the exception of a small amount that remained.

John Waa decided to buy a claim that he liked. He paid all of 50 dollars for the claim. I took a claim next to Waa’s, though I was still too young to take up land.[8] But the neighbors gave me counsel to do it, since they would see to it that no one could come and take my land from me.

My parents and siblings were still in Muskego. They would come after us, the following summer, and bring my oxen with them.

[1] “Red man” is a direct and literal translation of what Paulson wrote. Today, the term is widely considered to be an offensive description of Native Americans.

[2] Paulson writes the English word “half-breeds” here. It is widely considered to be an offensive term describing people who are of mixed race, and especially those who have one Native American parent and one non-Native parent.

[3] In Paulson’s book, this name is rendered as “Skapurong”, but it seems to be an error. Searches for “Skapurong” didn’t yield anything. But there was a Norwegian settlement called Skoponong that was in line with the other places Paulson names as their route to Decorah, Iowa. A Skoponong Church cemetery is still there today, in the countryside southwest of Palmyra, Wisconsin. A September 13, 1924, article from the Whitewater Register newspaper, from nearby Whitewater, Wisconsin, tells about the church and the settlement. It has been digitized by the Wisconsin Historical Society here: https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Newspaper/BA8261

[4] In this case, it seems certain that Paulson means U.S. miles and not Norwegian miles. Five Norwegian miles would be 50 kilometers, or about 31 U.S. miles. Later in the paragraph, the group is able to reach the doctor’s house in a morning’s drive and arrive there around midday.

[5] Paulson’s text says “Palengra,” but searches for a place by that name don’t turn up anything. I believe this is an error in the book and that Paulson meant to say “Palmyra.” For a farmer around Koshkonong, Palmyra would have been a relatively nearby place to go and sell grain. It lies on the way to Milwaukee and it would have required only one-half or even one-third the travel time to reach that Milwaukee did. In addition, it isn’t hard to imagine that an editor or typesetter could mistake a handwritten “m” for an “en,” and a handwritten “y” for a “g.”

[6] The Homestead Act was signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln on May 20, 1862.

[7] Paulson uses an old and colorful idiom here: Nå var vi i et par bukser (modern spelling). It means literally “Now we were in a pair of pants,” but it expresses being in a difficult situation. The origins of the saying are obscure and not easy to convey in a footnote, but they are explained by Magnus Bernhard Olsen on pages 164–165 of his 1909 book Maal og Minne, on folklore and language history. See the book, as digitized by the Internet Archive, here: https://archive.org/details/maalogminne1910olse/page/164/mode/2up?q=bukser

[8] Under the Preemption Act of 1841 (and later the Homestead Act of 1862), a person had to be either the head of household or at least 21 years old to claim land.

Translation of chapter from the Norwegian language into the English language, and preparation of footnotes, by Denise Logeland.