Reminiscences

of

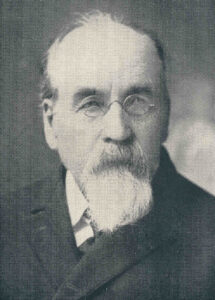

Pastor Ole Paulson;

1907 Autobiography.

Chapter One

A translation from the Norwegian language into the English language.

Copyright © 2022 by Gary C. Dahle, all rights reserved.

About the Journey to America

Up until 1850, there was no one who had traveled to America from Solør[1] in Norway.

In those days, very little was known of America in those parts. We knew just barely that a land existed where, according to popular belief, “roast pigs ran in the street with a knife and fork in their backs.” At any rate, the average Solung[2] was in possession of very poor information about the “far west.”

The year 1850 is far back in time! It was just 25 years after the famed sloop from Stavanger sailed over the Atlantic with the very first emigrants from Norway. The reports that the Sloopers sent home did not reach as far east as Solør. It was not then as it is now, that reading newspapers is common. Now, nearly every man knows, even on the same day, what is happening, and not only what is happening in one’s own country but also what is taking place over the entire world. The reason for this is the convenience of communications, the telegraph and the press. Half a century ago, it was not so. When we left for America, there was no railroad to be found in Norway and no telegraph, either.

Newspapers were few and far between in my home village, and if we had any, they were nearly as unknowing about America as we ourselves were. America was a land of fables, inhabited by wild men and natives, where there was neither law nor order. There, there was freedom for every man to do and be as he himself wished. In a word, it was a dangerous and uninviting country to come to.

I remember it as well as if it had happened today. Our little company of emigrants came rattling along with a two-wheeled cart[3] on the heights above Christiania.[4] There stood a little house at the side of the road. It was probably a tavern. The door stood wide open. Inside sat some men playing cards. When they noticed us, they called out: “Hi, good folk! Where are you going, then?” “To America,” I answered. “Ha, ha! To America? You’ll never get there,” one man added with a thick tongue. He probably meant that the captain would take us to Turkey and sell us as meat to the “Tryne-Turk.”[5]

It’s possible that the beer keg in the tavern wanted to play a joke on us, or he didn’t know any better.

My parents were common farmers. My father had great struggles to make both ends meet. Through an unfortunate farm deal, he had come into debt. He struggled mightily, the best he could, but he wasn’t able to meet his obligations as he should have. As long as the logging woods held out, it was still possible to get by, but now when the woods were giving out it began to go backward for him. Besides that, timber prices were so poor that the timber business was not much better than starving to death in Solør in those days. Still, the Solung kept on, like a horsefly on a bony mare. That was the case with my father, too. He had an attractive and, to be sure, a good farm, East Waalberg at Grue Finnskog,[6] a scant mile-and-a-half[7] from the Swedish border.

But the Solung, as a rule, neglected farming and worked himself to ruin with timber. One took the best of the food for the logging camp, so that when spring came and one had finished the spring chores, the storehouse was empty, and the wallet was just as empty. What could one do then for a living until harvest? Yo ho! The Solung had an answer. He hitched the mare to the cart and drove to Christiania. Here, he got food for the summer on credit or with a loan against the timber. He came home with every good thing for life and limb. He had loaded on as much as the mare could pull. Now there were means to live without worry until the harvest.

When winter came, it was off to the woods again to toil as much as the tools could withstand. It was the only way the debt in Christiania could be paid.

In this way it went, around in a circle, year out and year in. But the Solung was used to this slavery and sang just as merrily: “I am so cheerful, I am so glad, I am my own master.”

To improve his lot, Father exchanged his fine farm for another that was much poorer. Lintorpet, which we got, was a fairly good-looking farm with good houses, but it was meager and probably misused. Father could by no means manage here; it went the way the hen scratches.[8] One can imagine his state of mind with failure staring him in the eyes. He didn’t say much about it; quite the opposite, he seemed just as merry. Once one knew it, though, one could see that he was deep in thought.

In the early winter of 1850, he came home one evening rather late. After having eaten dinner and lit his pipe, he walked back and forth across the floor and smoked more than usual. At last it came out, the thing that weighed on him as he paced: “Mother,” he said, “do you know what I’m thinking about?” She answered: “How can I know what you have in your thoughts?” “Well, Mother, I am wondering about traveling with all of you to America!” he said. “No, now I’ve never heard anything so crazy,” she said. “You traveling to America with this big family. It must be the very height of insanity, to harbor such thoughts!”

Father walked back and forth with long steps and smoked as if it would help. And now he started in with bold eloquence. I don’t remember all that he said, but what I remember delighted me: “One would have to look high and low for such folk as you are. If I would and could lead you to Paradise, it wouldn’t be good enough, you’d have to put up a struggle against it. Enough said. I’m going, and you can stay behind if you want to.”

Mother did not answer but took up the usual weapon of women: crying.

This ended the quarrel.

Now each of us went to his bed and we slept in peace, without even dreaming about the Tryne-Turk and the wild people that America was supposed to be full of.

The next morning, I, as the oldest son in the household, had to hitch up the mare to the timber sledge and head out to the logging camp. I was slight of stature and not very old, either, not fully 18. It was bad enough for me that winter. I was tired, but I didn’t complain. As long as I had a good horse, it worked out, but into the winter father traded horses and got a little male, who was not much stronger than I myself was. For a time in the early winter, I had comrades in the camp. That was a fun time.

Later, I was alone at the camp, and then I have to say it was dreary. Every once in a while, I heard wolves howling at night. I shudder still when I think of it. In the morning, I had to go out around three o’clock. One had to make one trip before daybreak, and the other trip one had to do in the afternoon. It took not a small amount of time to load up, alone as I was. The timber I was driving belonged to a rich uncle of mine, Hendrik Tvengsberg.

One day, when I had made the first trip and had lain down to take a short afternoon nap, here comes my brother Hendrik, his breath in his throat, saying: “Father has sold Lintorpet and we are going to America.”

“Has Father really sold the farm and said that we are going to America?” “The deal is done and we’re going as soon as we’re ready, in a few weeks,” he said. “Has Father sent you here with the message?” I asked. “No, I came anyway. I knew you would want to know and so I came.”

“Are you happy about the America trip?” “I have never been happier.” “But what do you think about it?” “I’m so happy I could wheel and kick like a Halling[9] dancer.” “But now I have to leave,” he said. “At home, they won’t know what became of me.” “Wait a little bit, I’ll come along,” I said. Hendrik had a bit to eat, and then we loaded up the horse fodder and the food onto the sledge, and then we drove as fast as the worthless horse could go.

Father was standing outside and saw when we came driving up to the house. He was “upset.” “I mean, a boy has to be crazy who comes home with the fodder and doesn’t drive home the timber that remains. What is wrong with you, I have to ask.”

“Aren’t we going to America?” I asked. “Yes, of course we are,” he answered. “That is beyond happiness for me. Not one more log will I drive in Norway. Uncle can drive his timber himself.” I had so completely disarmed the old fellow that he just smiled and walked away, without saying another word.

In a few weeks, we were already prepared for the trip. It was as if Father was inspired by the thought of America. I believe he truly was. He got new life and new energy. In the short time that he had to get ready, he made a trip to Christiania to reserve space onboard a ship to cross the sea. He got an auction announced. Everything on the farm had to be sold under the hammer. He had errands with the tax collector and the judge. Astrup was appointed as the interim tax collector in Grue at that time. If I remember correctly, the judge’s name was Fitzen.

While Father was with the judge, who learned that he intended to go to America with his family, the judge said: “You are making the right choice, man. It’s much, much better there than here. Here, I’ll lend you a letter written by my half-brother, Candidate[10] Ole Rynning.[11] He went to America many years ago, as you will see in the letter. He became ill with cholera and died. But though he is dead, the truth of what he has set forth in his letter still lives. Take the letter with you home and study it closely. Every word he has written is true.” Father came home with the letter, beaming. As I was the one in the family who was best at reading print, I read the remarkably long letter over and over again, so that I almost could recite it by heart. Everyone who came into the house had to hear Candidate Rynning’s letter.

Now, we were no longer unknowing about America. We believed the letter and found that each word was true, as the judge had said. On the 17th of May, 1850, we began our journey through our home village, Grue. The worst thing was that Mother and my little sister, Anna, had to stay behind because our travel fund was too small. Some of us others could have stayed back, but Mother wanted that we should go. She would come the next year, when she had received some auction and other monies that could not be collected before we left.

Those two dear ones came the year after and found us in Muskego. We will hear more about Muskego later.

When Father came to Christiania, all of the America ships had departed. But merchant Christian Hassel in Christiania and his two brothers, Christoffer and Petter Hassel, who both lived in Kragerø, owned a new ship, the Colon, which was going to sail on the 15th of June with emigrants, from the last-named place to New York. Father signed up himself and his family as passengers on the Colon, led by Captain Christoffer Hassel, a particularly able skipper. The fare was paid from Christiania; the shipping company therefore had to transport us to Kragerø, which it did in a pretty modest manner.

We embarked from Christiania to Kragerø on a tiny little sloop, old and to be sure dilapidated. The journey took us a full nine days. However, the trip was fairly enjoyable out through the lovely Christiania Fjord, past the many pretty small towns.

We were blessed with especially favorable weather, with the exception of one Saturday afternoon when we sailed out from Moss, where we had lain a couple of days to take on two enormous water casks that were to be taken to the ship Colon. On the broad fjord outside of Moss, we met with a severe storm, so that the sloop had to turn and run to the lee of Vartøyen, where we stayed the night and over Sunday. Here we fished and ate raw oysters, the first and last raw oysters I’ve ever eaten.

It was a sunny day when we came gliding into the wharf in Kragerø and laid up alongside the Colon. Captain Hassel stood on the deck and was in a lather that the trip had taken so long. Even now, I can see the captain’s stern and manly form and hear his coarse, bellowing voice, as he addressed our skipper: “Are you finally coming now? What have you been doing, that it has taken you an entire nine days to come from Christiania to Kragerø, a distance that you should have put behind you in less than two? Did you want to plague the life out of these folks, who were unlucky enough to have to travel with you?”

He said this in a voice that was entirely a match for his seamanlike nature and character.

The skipper, poor fellow, was probably used to such things. He took it in stride and mumbled something about still winds that he couldn’t help. “You are really a lout, I’d say,” the captain added. “See to it now that you get the people out of your miserable washtub,” he said further.

We got out in a hurry and onto the ship that would now be our home for the span of two and a half months.

The ship was still not quite ready. The carpenters worked with all their might on fitting out the cabin to get it done.

We were shown to our place by the captain himself at midship, just under the large hatch the led up to the deck. This was the best place, in the captain’s opinion.

In a couple of days came the rest of the emigrants who would make the journey over the sea with us. Most of these were farmers from Telemark, especially from Søvde Parish, Siljord, and Bøhered.[12] Only a few people were from as far up as Rauland and Vinje.

We completely went to pieces over the appearance of these people. We had never dreamed that in Norway there should exist people of such peculiar appearance as these Telemark farmers. It was especially those from lower Telemark who awakened our astonishment the most. The men were all dressed alike, as if they were uniformed soldiers. All of them had black knee breeches, silver buttons at their knees, long white stockings with embroidered roses at the ankles, low shoes with ornamental stitching, a strangely ugly white jacket decorated with red and blue, a vest likewise bedecked with silver buttons and embroidered in an odd manner with red and blue, a cap that closely resembled the one that railroad functionaries have here in America, but with the difference that there hung a large tassel from the crown of the cap and down over the right ear.

The women were dressed in an especially ugly way. All of them had a thick black wadmal[13] skirt that reached all the way up to their underarms. Around their middles, they had a long wool sash that was wrapped several times around their waists. They had a short jacket of wadmal. On their stockings was an immense amount of decoration, with embroidered roses at the ankles, of course, and low shoes that had decorative stitching. The garment on their heads was some kind of kerchief.

What we heard and saw of these people was just like a theatrical play for us. Their language was so entirely different from our eastern one that we had a hard time understanding them at first. But we learned quickly. It didn’t take many hours before the Telemark farmers had to have a dance. The spelemann, or playing man, as he was called in their language, came forward with his strange doodad of a fiddle, adorned with mother-of-pearl on the edges and eight strings.

When he had tuned up and struck up a melody, the girls began to tap their feet to the beat. The young men couldn’t stand by and watch, so they came running and invited them to do a gangar or springar,[14] and there was a hullabaloo so that the dust flew about our ears.

Now the fiddler struck up a Halling. “Where is Tarje?” Everyone called out for Tarje. Yes, there came the Halling dancer himself, truly a singularly comical figure. Small in size, bowlegged, hunched over, with a long face, laughing eyes, a great long, crooked nose, and long hair. He constantly wore a red stocking cap. Tarje was always full of jokes and fun. Now he came hopping across the deck, leaping and kicking with his legs in time to the beat of the fiddle tune. The deck was immediately cleared. He hopped right up into the air, turned around like a top, and cast himself so that his legs were up above and his head almost down on the deck, and still he came down with his feet on the deck so that it clattered. There was shouting and laughter and clapping of hands for Tarje.

One day, when we had come a ways up into the Erie Canal, Tarje had been in the canal to take a bath. It was close to a little town. When he had come up out of the water, he didn’t put his pants on, but strolled right through town without any other clothing than his long Norwegian shirt. People in the town gathered in a flock and stood and watched the mad man. They believed without doubt that the man was crazy.

For us easterners, all of this was something so new, it was as if we had left Norway and Norwegian surroundings, as if we all at once had been placed among nothing but complete strangers in another part of the world.

Kragerø was at that time a fairly small town with perhaps 1,000 residents, pressed up against the wall of the mountain. The streets were narrow, crooked, and cramped. The houses were built up along the side of the mountain. It almost looked as if they were built on top of each other. Down by the fjord was a flat strip of land where the church and the businesses stood. The city had, however, some fairly lively shipping traffic. There were so many ships in the harbor, especially many Dutch vessels.

I liked it so well in this little town that if not for the fact that we had decided to go to America, I would have stayed there.

In Kragerø, I saw a negro for the first time. It was merchant Henrik Bjørn’s negro. The negro stood in the woodshed and split wood. A flock of us emigrant boys stood in the doorway and stared intently at him. He got angry, swore in Norwegian, grabbed his axe, and came at us with it, as if he wanted to use it on us. We were so scared! We felt as though the devil[15] incarnate was after us. We ran with every fiber of our being to get away from the monster.

About the trip from Kragerø to New York there isn’t much to tell. In life at sea, one day is like the next, especially when the weather is even and lovely, as it was during our trip.

The Colon sailed out from Kragerø on the 15th of June, 1850. As soon as we got out onto the open sea, we had a fairly brisk breeze, so that the ship rolled rather violently.

On the wings of the wind, we sped past the coastal towns of Arendal, Christiansand,[16] and several others. Soon we were on the North Sea and Norway, our old Norway with its “fortress of stone,” fell out of our sight.

I have not seen it again since. One has strange feelings when one is about to leave the country of his birth. One stands and stares at the gray cliffs for as long as they are visible over the rim of the sea. One hangs onto the the sight of the cliffs until it sinks into the sea and is gone. One thinks with melancholy of the song: “Wherever in the world I go, whether south or whether west,”[17] et cetera.

Now there was a tremendous situation in the ship’s hold. The people had been gripped by seasickness. One after another came running up onto deck, stretched their neck out over the bulwark, and delivered up from themselves all unnecessary ballast. From every quarter, yammering and whimpering were heard. I stayed up on deck among the sailors until far into the night and avoided seasickeness. Now there were many who wished they were back in Norway. People don’t tolerate the smallest adversity. Captain Hassel knew the sea as well as a Dakota farmer knows his farm. For many years, he had sailed another ship by the name Columbus and had made many trips with emigrants to New York. Now he set course for the English Channel. In a couple days or so, we were in the channel. To our right we saw England and to our left France, only that there wasn’t much to see, just the naked, white chalk cliffs. Soon this sight was also gone from view, and we were rocked on the waves of the Atlantic Ocean. Now all sights were gone for about eight weeks, with the exception of one or another sailing vessel that we might coincidentally meet at sea.

As we neared the banks of New Foundland, we passed close to an iceberg one morning. All at once, it got as cold as in an ice cellar. The Colon sailed fairly close to the troll, which stuck up out of the sea perhaps 200 feet and had a fairly large circumference.

A couple of days before we came to New York, the captain took a coastal pilot onboard. Now all things went well; we reached this city of the world in good shape. Just one woman, the wife of the spry Halling dancer, lay sick when we arrived; she was ill the whole trip with seasickness. No one was born and no one died on the journey.

When we came to New York, we had been at sea for eight weeks and two days. The actual reason that it took so long was still winds and headwinds. There were others ships that were at sea for 10 to 12 weeks. Ships that had sailed before us came to New York after us. So in that regard, we counted ourselves fortunate.

As we lay rocking on the Atlantic’s waves, the time was often oppressively long. As a pastime, the captain came up with certain gymnastic exercises for us. He himself was a rather spry man yet and a good gymnast. We had to do many kinds of exercises. And then he would round us all up on the deck, when the weather permitted. The fiddler had to come out with his fiddle, and the Telemark farmers had to get in a gangar or springar. Tarje had to also come out and show how flexible he could be and how high he could kick.

Still, it was as though nothing would go. When one is idle for so long, one gets so lazy that after a while one doesn’t want to do anything. There were no oaths or swearing onboard, no card playing or drinking spirits, either.

On Sundays we had devotions. The captain rousted everyone up on deck, which was arranged so that people could sit. We sang hymns from Guldberg,[18] and the captain himself read the sermon. There was no one who could lead us in prayer.

New York was already at that time a beautiful, big city with many sights to see. The most eyecatching was the harbor, where there were hundreds of ships from all parts of the world. The many masts looked like a thick forest of spruce in Solør. In the evening, it was especially a sight to see the large steamships that sped back and forth, lit up as they were with hundreds of lamps. They looked to our eyes like floating pleasure palaces.

We lay in New York for just one day. The captain was our interpreter and helped us to get inexpensive fare to go further on our way. He knew our situation, that we were mostly all poor, with the exception of Rich Rollef, as he was called. He had, like a real skinflint, laid some money up for himself, as filthy and ragged as he nonetheless looked. A few of the Sauherings[19] had, perhaps, some hundreds[20] saved up to start life with in America.

I don’t remember how much we paid per head from New York to Milwaukee; it seems to me that the ticket was seven dollars. But if the fare was cheap, the transportation was in keeping with it. In those days, one hauled emigrants in about the same way that one hauls livestock today. We were taken by steamship from New York to Albany, and from there to Buffalo over the Erie Canal, and from Buffalo to Milwaukee by steamship.

On the canal, the whole party was squeezed into a single canal boat with baggage and all. First, the cases were packed down into the boat, then equipment on top of that, and people on the very top. Luck was better than wits that time. The weather was at its very best the entire time, so that time could be spent on the deck both day and night. If we had met with rain or thick fog, I don’t know how it would have gone with us. Probably sickness would have broken out among us. Now, we could sleep on the deck at night without taking any harm from it. A heavy dew fell on the canal at night, which made it just a bit unpleasant.

We spent a full nine days on the canal. From Buffalo to Milwaukee by steamship took us four days. In all, the trip took us 14 days from New York to Milwaukee. Now people travel from Christiania to America in less time than that.

The whole trip to America took us from the 17th of May to the 22nd of August, when we landed in Milwaukee. The company arrived in Milwaukee in the late afternoon. Here, we spread like chaff on the wind. Of all of our party of travelers, I have only met four or five people again in these 56 years, namely: Bjørn Aslakson Svalestuen, Ole Rauland from Raulandsstranden, and the brothers Ole, Thor, and Kittil Støilen. The three first named are dead, and the last two live in Perry, Dane County, Wisconsin, and are in the best of health.

Having arrived in Milwaukee, we could not obtain housing for the night. The city was under quarantine, as cholera was raging there. We had to take refuge among our cases on the street. Such was our fate in the promised land of America. All of the people were afraid of newcomers.

The next day, we got a Norwegian farmer to take our things, and we followed him on foot 22 miles to Muskego, the place where the emigrants often stayed for a while.

We, which is to say my family, followed along with our companions from Raulandsstrand to Knud Aslakson Svalestuen, who lived a short ways from Waterford, Racine County, Wisconsin. Knud had been in America already for some eight to 10 years and lived on a nice farm, which he owned. He had already, some time before this, made a trip to the Old Country and had come back several years ago.

Here our America journey ended for the time being.

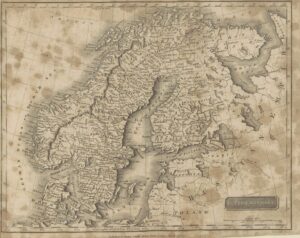

[1] Solør is a region in the Glomma River valley in eastern Norway. It’s located in present-day Innlandet County, between Elverum and Kongsvinger. It includes the communities of Grue, Åsnes, and Våler.

[2] A Solung is a person from Solør.

[3] The Norwegian word here is kjæreskyds, which does not appear even in dictionaries that include archaic Norwegian words and does not turn up in searches of 19th century writings. The second part of the compound is recognizable as skyss (modern spelling), meaning “transport” or “ride” or “conveyance.” I believe the first part of the compound is an old or dialect spelling of the modern-day word kjerre, which refers to a small, two-wheeled cart.

[4] Christiania is a past name for present-day Oslo.

[5] The Norwegian word Trynetyrk is an archaic word for “Turk,” but also, as in Paulson’s use here, a mythical figure, a man-eating being with a pig snout that was referenced by author Henrik Wergeland (1808–1845).

[6] Grue Finnskog is a parish in the municipality of Grue in present-day Innlandet County in Norway.

[7] The Norwegian word here is fjerding, an archaic term for one-fourth of a Norwegian mile. A Norwegian mile equals 10 kilometers; a fjerding equals 2.5 kilometers or 1.6 U.S. miles (1 km = 0.6214 miles).

[8] In Norwegian, to say that things are “going the way the hen scratches” means that things are going backward or going badly; “going to the dogs,” we might say in English.

[9] The Halling is a dance characteristic of the Hallingdal region in present-day Viken County, in the municipality of Buskerud, Norway, northwest of Oslo. The dance, done by men, features high kicks that aim to knock down a hat held high on a pole.

[10] “Candidate” can mean a political candidate but also, as in this case, a person who has taken university exams.

[11] This appears to refer to the famous Ole Rynning who was a founder of the early Norwegian settlement at Beaver Creek, Illinois, in 1837. Rynning died the next year, but during his only winter in the United States, he wrote what became an influential guide for those in Norway who wanted to emigrate, a book called Sandfærdig Beretning om Amerika til Oplysning og Nytte for Bonde og Menigmand (True Account of America for the Information and Use of the Farmer and Common Man). Rynning was an uncle to St. Olaf College founder Bernt Julius Muus. Source: Store Norske Leksikon (snl.no), an online encyclopedia managed by a consortium of Norwegian universities. See Rynning here: https://nbl.snl.no/Ole_Rynning

[12] These are archaic or dialect placenames for parishes or districts in the county formerly known as Telemark (today called Vestfold og Telemark). Siljord = present-day Seljord, Bøhered = a district around the present-day city of Bø, and Søvde Parish = Saude Parish or Sauherad Parish, a rural district to the east-northeast of the present-day city of Nesodden. See a map of old Telemark parishes here, on the FamilySearch genealogy website of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints: https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Telemark_County,_Norway_Genealogy

[13] Wadmal is a type of coarse woolen cloth traditional in Scandinavia and in the British Isles.

[14] Gangar and springar are two types of Norwegian folk dance. A gangar is in 6/8 time, a springar is in 3/4 time.

[15] The Norwegian phrase that Paulson uses here, den skinnbarlige selv, could be translated literally as “the incarnate one himself.” It’s an old-fashioned way of referring to the devil “in the flesh,” or the devil incarnate, without having to utter (or write) the word “devil.”

[16] Today the name of this city is spelled “Kristiansand.”

[17] Paulson quotes the first line of a poem here, “Mitt fødeland” (My Native Land) by Andreas Munch (1811–1884). The poem was set to music and appears in at least one songbook, published in Norway in 1903. But the song was likely well known earlier than that.

[18] This refers to a hymnal produced under the direction of Ove Høegh-Guldberg of Denmark, and published in 1778. Guldberg was a political leader and an influential counselor to King Christian VII.

[19] Sauherings refers to people from Sauherad, a former municipality in the east-central part of the present-day county called Telemark og Vestfold.

[20] The meaning of “hundreds” here is unclear. Paulson might mean hundreds of U.S. dollars or hundreds of Norwegian speciedaler (also spelled spesidaler), the main monetary unit in Norway in 1850. (The krone, or crown, was introduced in the 1870s.) Using a conversion table from Norges Bank, the central bank of Norway, 300 Norwegian speciedaler converts to 1,200 Norwegian kroner. That amount is equal to about US$124, using a present-day exchange rate of 9.7 kroner to the dollar. At present, however, the Norwegian krone is unusually weak relative to the U.S. dollar, so a present-day conversion rate might be misleading. One historical currency converter, produced by Professor Rodney Edvinsson at Stockholm University, pegs the 1850 value of NOK1,200 (a stand-in for 300 speciedaler) at US$320—which appears to show that speciedaler were roughly equivalent to U.S. dollars in 1850. Sources: https://www.norges-bank.no/en/topics/Statistics/Price-calculator-/ and https://www.historicalstatistics.org/Currencyconverter.html

Translation of chapter from the Norwegian language into the English language, and preparation of footnotes, by Denise Logeland.