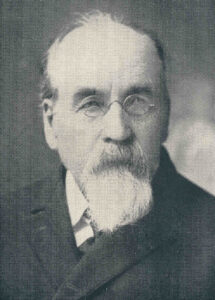

Reminiscences

of

Pastor Ole Paulson;

1907 Autobiography.

Chapter Thirteen

A translation from the Norwegian language into the English language.

Copyright © 2022 by Gary C. Dahle, all rights reserved.

1862; To War

The war of rebellion was at its height in 1862. The events of the conflict were proof that the Rebels were not to be trifled with. They were well-prepared for a war with the North. A large share of the Army’s officers had joined the Rebel forces. Arsenals and forts had fallen into their hands. The nation woke from its torpor when Fort Sumter was attacked and, after a short battle, fell into the Rebels’ hands on April 14, 1861, some six weeks after President Lincoln’s inauguration on March 4, 1861. This event opened the bloody drama that now ensued for four long years, before General Robert E. Lee surrendered to General Grant on April 9, 1865. As mentioned above, the war was at its height in 1862. The North’s army was very unlucky to begin with and suffered defeat again and again. Sometimes they were very humiliating defeats, as, for example, the two battles at Bull Run and McClelland’s campaign against Richmond on the peninsula. This campaign was an absolute failure.

The Union Army won the battle at Antietam. But then General Burnside was given command of the Army of the Potomac and lost a brutal battle at Fredricksburg. He was pulled immediately from command and General Joe Hooker replaced him. General Hooker attacked Lee at Chancellorsville[1] and suffered a terrible defeat, with a loss of 17,000 men. Such was the situation of the Army of the Potomac. It seemed as if the Potomac was our ailing toe. It went better in the West.

However that may be, more men were needed. But then the president had presumed as much. In the month of June, he called up 300,000 men, and in August he needed 300,000 more, in all 600,000 men in the summer and autumn of 1862. We sang as we marched: “We are coming, Father Abraham, six hundred thousand more.”

In July and August 1862, there was an agitation that nearly reached the level of a panic. Recruiting was taking place in almost every county across the whole country. The recruitment officers traveled around with drums and fifes, in cities and in the country, drumming folks into meetings, where inciting speeches were given with the aim of generating enthusiasm and the intoxication of war in young men’s bosoms. The situation in the theater of battle was not promising, and a duty rested on all who were capable of using a weapon to come to the aid of the bleeding nation. One had to set aside all other considerations and join the ranks of the brotherhood who fought. The cowards could stay home or go to Canada. There were, indeed, some who headed for the woods and across the border into Queen Victoria’s possessions. There were also those who maimed their own limbs, for example cutting off a finger or a toe to avoid service in the war. I knew one person who, when he learned that he had been drafted, went out to the woodpile, put his foot on the chopping block, and cut off his big toe, but nearly lost his life due to bleeding.

There were still recruits to be had; there was no need yet to proceed to conscription. But 600,000 men was a large army. Did anyone really think that such an enormous army of young men would willingly join the ranks of those fighting in so short a time as scarcely six weeks? Yes, that was the idea and this idea was realized. On the 22nd of August, 1862, at midnight, the number was reached. Six hundred thousand[2] young men, of all social classes—farmers, handworkers, merchants, lawyers, pastors, students, young and old—had by that stroke of the clock given their oath of loyalty to Uncle Sam and taken up arms for the defense of the beloved fatherland. This was almost certainly something that was entirely unique in the history of war. But the enthusiasm was, indeed, great. The departing multitudes sang, as mentioned: “We are coming, Father Abraham, six hundred thousand more.”

Two recruiting officers came into our settlement, William R. Baxter and Joseph Weissmann, both lawyers in the city of Chaska. One was an American, the other a German. They gathered people, preferably in the evening, and gave speeches to them. The majority of the Scandinavians did not understand English. These officers then turned to me for help. Since I regarded myself as a natural choice to remain at home, because I was a theological student, I thought that I ought to do at least this much for the defense of our country. I went with them and held thundering speeches that were overflowing with love of country. As a result, many of my friends, relatives, and neighbors allowed themselves to be reruited. But wait! As I spoke to the others, I spoke also to myself and was smitten by war fever; but I was not going to allow myself to be caught by it, no indeed! Wasn’t I a natural choice to remain at home?

The 22nd of August was set as the date on which the 100 dollar bounty for recruits—incentive money to enlist—would expire. The next morning the boys would travel by steamboat from Carver to Fort Snelling to be mustered in. I started to feel a little strange at the thought that so many of my warmest friends and dear ones were going to leave. I wanted, at least, to go into town to bid the dear departing ones a last farewell. When I left that evening, Mrs. Paulson said: “You must not go to war,” she said. I answered, “You know that I am an obvious candidate to stay at home with you, my little girl. I have a higher aim in mind than to become a soldier.” I left with the thought of coming home in a few hours.

Arriving in town, I found excitement beyond description. The recruiting was going on at a brisk pace, but suddenly it came to a halt. There were no more who looked amenable to going. There were still 14 men lacking to form a full company. There were quite a few standing near me who wanted to go if I went. The majority of these were serious young men, members of the same congregation as me, namely Pastor Carlson’s. There we stood arguing for a long time. It was drawing close to the time when the recruiting would end, namely 12 o’clock. I tried every possible excuse, for I was, of course, an obvious candidate to stay at home. I appealed to their consciences as Christian men, asking whether it was right for me, as a theological student, to become a warrior. I was determined to go to school again in one month’s time. It didn’t help; my objections were in vain. “I was just as able as them and just as obligated as them to take up arms to help save the country from collapse and ruin.”[3]

Yes, but I was going to school in a month. “That’s just an excuse. We’re going to go down south and whip the Rebels. In a few months, we’ll come home again and then you can go to school. What do you say to that?” “I say that I cannot go.” “Listen, now! Isn’t he a coward?” shouted some of the others. “You’ve stood now evening after evening and preached to others about their duty to hasten to aid of the bleeding country and the brethren who are fighting. We’ve acknowledged the rightness of your words, and now we are here, ready to go, but we want you to go with us. You come with empty excuses, which proves that you are a coward, you are afraid!” I have to admit that the blood began to boil in my head; I was angry.

“Can I be sure that you will go and do the same if I go first and swear the oath of allegiance?” “You can be sure,” they shouted with one voice. “I don’t dare to trust you. If I go forward and say the oath, then you all have to come so that we give the oath at the same time. What do you say to that? Are you all ready?” “We are ready, hip, hip hurra!!” And 15 men of us raised our hands in the air and swore our allegiance to Uncle Sam unto death. Many of these 15 lay buried in the earth in the South.

There I stood and could not go home that evening and tell my wife how it had gone, that I was going to war and had put on Uncle Sam’s uniform.

Did I find peace in this step that I had taken? I had a terrible night of reproaches from my conscience and spiritual agony. It seemed to me that I had rebelled against God and fallen away from him because I had unnecessarily cast myself into temptation. I cried out to God from the depths.

I probably realized that I had not sinned by taking this step, but it struck me as wrong, that I, who felt certain that God had called me with a sacred call to preach the Gospel, now all at once interrupted the path that God had laid for me. It was quite a long time before I found peace, and then mostly in the thought that perhaps this was God’s plan. It was perhaps God’s will that I should not become a pastor. Here, I found peace for my soul.

We went into service on the condition that we would have 14 days leave at home after we had been to Fort Snelling to organize the company.

Early the next morning, we went by steamboat from Carver to Fort Snelling. On the way down the river, a man came to me and asked “if I wished to become a lieutenant.” I answered “that I hardly knew what a lieutenant was.” “You know as much as anyone else in the company,” he answered, and continued: “There are enough Yankees in the company to cover all of the positions of trust, which, indeed, they are after. But half of the company is Scandinavians. You ought to lay claim to at least one-third of all the officers’ posts, from captain down to the last corporal. I suggest that you Scandinavians hold a caucus and come to agreement about a list of posts that you wish to be selected for.” This man was an Englishman who went with us to the fort, but he did not belong to the company. I found his suggestion to be quite sensible. We had our caucus. Baxter was recommended for captain, Weissmann[4] for first lieutenant, and Ole Paulson for second lieutenant, and so on, so that every third officer down to corporal was a Scandinavian.

There were several who desired the first two posts; I had no opponent and was elected unanimously. In other words, we Scandinavians were able to elect our slate because we were a majority and were in agreement.

On September 1, 1862, I accepted the commission issued by Governor Alexander Ramsey as second lieutenant of Company H of the Minnesota Volunteers 9th Regiment. Now we all had leave at home. A strange alteration had taken place with me. I came home with a military cap on my head and lieutenant’s epaulettes on my shoulders. It was, in fact, the only military distinction we had had time to adopt as yet.

[1] The Norwegian text says “Chansorville,” most likely a misspelling of Chancellorsville, a battle where, as Paulson says, Hooker led an attack against Lee’s army.

[2] The words “six hundred thousand” here are in boldface type.

[3] This quoted sentence looks a little odd, because Paulson is quoting the friends who stood around him and argued that he should enlist, but he’s doing it in the first person, saying “I” instead of “You” as they would have.

[4] The name has been spelled with one “s” here in the original text, though the first time Joseph Weissmann was mentioned, earlier in this chapter, his name was spelled with two “s”s. The spelling of his name fluctuates throughout the book, sometimes with one “n” or two, sometimes with one “s” or two. I’ve consistently used the first spelling I saw, two “s”s and two “n”s.

Translation of chapter from the Norwegian language into the English language, and preparation of footnotes, by Denise Logeland.